유전자 교정한 아기를 태어나게 하는 데 성공했다고 주장한 허젠쿠이 중국남방과기대 교수. – 사진제공 중국남방과기대

중국 과학자가 세계 최초로 유전자 가위를 이용해 유전자를 교정한 인간 아기 출산에 성공했다고 주장했다. 아직은 동료평가(peer review) 등을 거치지 않은 일방적 주장이지만, 만약 사실일 경우 과학계가 암묵적 ‘금기’로 여기던 ‘디자이너 베이비(원하는 대로 유전자를 수정해 탄생시킨 아기)’를 만든 것으로, 큰 윤리적 논란을 불러 일으킬 것으로 보인다.

25일(현지시각) 미국의 과학·기술 매체 ‘MIT 테크놀로지리뷰’와 26일 AP 통신 등을 종합하면, 허젠쿠이(�:建奎) 중국남방과기대 교수(사진)는 불임 치료 중인 부모 일곱 명으로부터 배아를 얻어 유전자 교정을 했다. 연구팀은 그 중 한 쌍의 부모로부터 쌍둥이를 얻는 데 성공했다. 어떤 교정이 있었는지에 대해 허 교수는 “유전병을 치료하거나 예방할 목적이 아니며, 에이즈를 일으키는 HIV 바이러스 감염에 저항성을 갖도록 하는 희귀한 형질을 갖게 했다”고 밝혔다.

허 교수가 26일 중국임상센터(HhCTR)에 올린 문서 ‘인간 배아를 대상으로 한 HIV 면역 유전자 CCR5 유전자 교정의 안전성 및 효용성 평가’에 따르면 22~38세의 부부를 대상으로 HIV와 천연두, 콜레라 등과 관련이 있는 CCR5 유전자를 유전자 교정을 통해 제거했고, 이렇게 교정한 배아를 자궁에 착상시켰다. 이 사실을 최초 보도한 ‘MIT 테크놀로지리뷰’의 기사에 따르면, 허 교수는 실험이 성공했느냐는 기자의 메일과 전화 질문에 답변을 거부했다. 하지만 이어진 AP 통신과의 대화에서 이번 달에 한 쌍의 여성 쌍둥이를 낳았다고 답했다.

현재 허 교수의 주장에 대해서는 동료평가 등 교차 검증이 이뤄지지 않은 상태다. 학술지에 발표하지 않았고, 화요일부터 홍콩에서 열릴 유전자 교정 학술대회에 앞서 대회 조직위원회에 결과를 먼저 공개했다. 이어 AP 통신과의 단독 인터뷰에서 다시 한번 연구 결과를 확인했다.

이에 앞서 중국은 2015년 4월에 이미 크리스퍼를 이용해 인간 배아를 실험실에서 교정하는 데 처음 성공해 학술지 ‘단백질과 세포’에 정식으로 발표하면서 격렬한 생명윤리 논쟁을 일으켰다. 많은 과학자들은 당시 연구 결과가 공개되기 한 달 전에 학술지 ‘네이처’를 통해 인간 배아 연구에 유전자 교정 기술을 쓰면 안 된다고 밝힌 참이라 파문은 더 컸다. 결국 그 해 12월 초, 미국국립과학원과 영국 런던왕립학회, 중국과학원 등이 함께 ‘인간 유전자 교정에 관한 국제 회담’이 열리게 된 계기가 됐다.

이번 연구는 아직 정식으로 동료 평가를 기다리고 있어 성공 여부를 논하기 어렵다. 하지만, 연구 결과에 앞서 배아를 직접 교정해 실제 아기를 태어나게 하는 실험이 진행되고 있다는 사실만으로도 큰 충격을 불러 일으킬 것으로 보인다. 이번 연구의 구체적인 전모는 화요일부터 진행될 학술대회에서 드러날 전망이다.

원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~

中 과학자 “수정란 교정” 주장… 중국 과학자들, 비난 성명 발표

학계선 “연구 중단하라” 요구도

중국에서 유전자 가위로 DNA를 교정한 아기가 출생했다는 주장이 나오면서 세계 과학계가 거센 후폭풍에 휩싸였다. 유전자 가위는 특정 유전자를 마음대로 잘라내고 교정할 수 있는 효소 단백질로 차세대 유전질환 치료 기술로 각광받고 있다. 하지만 아직 대부분 국가에서는 유전자 교정 아기의 출산을 허용하지 않고 있어 향후 윤리 논란이 거세질 전망이다.

지난 26일(현지 시각) 중국 선전 남방과기대의 허젠쿠이(賀建奎) 박사는 유튜브 영상을 통해 “유전자 가위를 이용해 에이즈(AIDS·후천성면역결핍증)에 면역력을 갖도록 유전자를 교정한 쌍둥이 아기가 탄생했다”고 발표했다.

허젠쿠이 박사는 유전자 가위로 사람 수정란에서 CCR5 유전자를 작동하지 못하도록 했다고 밝혔다. CCR5는 에이즈를 일으키는 HIV 바이러스를 사람 세포 안으로 들여보내는 단백질 생산에 관여한다. 과학계에서는 연구가 어느 정도 성공한 것으로 받아들이고 있다.

허젠쿠이 박사의 발표와 동시에 비판이 쏟아졌다. 중국 선전시 의료윤리전문가위원회는 같은 날 허젠쿠이 박사에 대한 진상 조사에 착수하겠다고 발표했다. 당초 알려진 것과 달리 해당 연구는 학교 측의 허가를 받지 않았던 것으로 확인됐다. 남방과기대 측은 “이번 연구는 학교와 아무런 관련이 없으며 학교 연구시설에서 이뤄지지 않았다”며 “심각한 윤리 위반이자 학계 기준을 어긴 행위”라고 발표했다. 허젠쿠이 박사는 연구 결과를 국제 학술지에 발표하지도 않았다.

학계의 비난도 거세다. 중국 내 과학자 122명은 공동 성명을 통해 “이번 연구로 중국 생명과학 발전에 큰 타격을 입었다”고 비판했다. 3세대 유전자 가위 기술인 크리스퍼의 창시자인 펭장 미국 매사추세츠공대(MIT) 교수도 “이번 연구가 비밀에 부쳐진 채 진행된 데 대해 심히 유감”이라며 “유전자 교정 아기 연구의 모라토리엄(중단)을 요구한다”고 말했다.

원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~

[유전자 편집 아기 논란]점입가경 ‘유전자 편집 아기’

윤리 논란 이어 “다시 보자”신중론까지 등장

허젠쿠이 중국 난팡과학기술대 교수가 28일 홍콩에서 열린 콘퍼런스에서 유전자를 수정한 쌍둥이 아기를 태어나게 하는데 성공했다고 밝혔다. AP/연합뉴스

출산 사실이 공개되면서 과학계는 물론 전 세계적으로 큰 파문이 일고 있는 유전자 교정 아기 연구 문제가 새로운 국면에 접어들고 있다. 연구자인 허젠쿠이 중국 난팡과기대 교수 자신이 28일 홍콩에서 열린 인간유전체교정 국제회의에서 언론 보도를 통해 알려져 있던 유전자 교정 아기 출산 사실을 공식 인정한 가운데, 중국 정부는 물론 세계 대다수 학자들이 이에 대한 부정적인 입장을 공개적으로 밝히고 있다. 하지만 조지 처치 미국 하버드대 교수 등 일부 연구자들이 허 교수를 옹호하는 뜻을 밝히면서 논란이 길어질 것이란 분석이 나온다.

허 교수는 인간 배아를 대상으로 에이즈 감염에 관여하는 단백질 CCR5를 제거하는 실험을 했다. HIV 감염 경로를 차단시켜 질병을 예방하게 한 아기를 태어나게 하려 했다는 게 허 교수의 주장이다. 언뜻 중요하고 숭고한 의학적 목적을 지닌 시급한 연구를 성공시킨 것 같다. 하지만 크게 두 가지 면에서 큰 비판과 논란을 낳고 있다.

먼저 인간 배아에 대한 유전자 교정 또는 수정 실험은 배아가 착상될 경우 실제로 유전자가 교정된 인간이 탄생할 수 있다는 점 때문에 강력한 윤리적 논쟁을 불러일으키는 주제다. 배아는 여러 국가에서 오직 희귀병이나 난치병을 치료하기 위한 기초연구에만 예외적인 연구를 허용하고 있다. 한국은 이조차 법으로 정해진 특정 질환에만 허용될 만큼 엄격히 규제되고 있고(포지티브 규제), 특히 배아나 생식세포를 유전적으로 변형시키는 유전자 치료는 아예 금지돼 있다.

최신 유전자 교정 기술인 ‘크리스퍼’는 워낙 강력한 유전자 교정 능력을 지니고 있기 때문에, 이 기술이 인간 배아를 수정하고 이를 바탕으로 디자이너 베이비를 탄생시킬 가능성을 연구자들도 잘 알고 있었다. 이에 2015년 12월 초, 미국국립과학원과 의학원, 영국왕립학회, 중국과학원 등 유전자 교정 연구를 선도하는 여러 국가의 연구자들이 자체적으로 미국 워싱턴에 모여 유전자가위를 사용했을 때 벌어질 수 있는 윤리적 문제를 자체적으로 논의하고, 자체적으로 “사회적 합의가 있기 전에는 유전자 가위를 이용해 교정한 인간 배아를 응용하지 않게 하자”는 성명을 발표했다. 이 때 응용이란 다름 아니라 실제로 유전자를 바꾼 아기, ‘디자이너 베이비(유전자 맞춤형 아기)’의 탄생을 의미한다.

하지만 이번 허 교수의 연구는 이런 합의를 사실상 무단으로 깼다. 배아를 아무런 사회적 합의 없이 착상시켜 실제 아기를 태어나게 했다. 중국은 인간 배아를 유전자 교정한 첫 번째 논문을 2015년 초에 발표해 세상을 놀라게 했을 만큼 인간 배아 교정 연구가 활발했던 나라다. 하지만 그런 중국에서도 그 배아를 착상시켜 출산에 이르게 하는 일은 충격으로 받아들여지고 있다. 크리스퍼를 진핵생물을 대상으로 확립한 이 분야 석학 장펑 미국 브로드연구소 교수는 소식이 알려진 직후 ‘MIT 테크놀로지 리뷰’를 통해 강한 비판을 가했다. 그는 중국에서 행해지는 비밀 프로젝트에 “깊은 우려”를 표하며 “교정된 배아의 이식에 대해 모라토리엄을 선언하겠다”고 말했다.

급기야 쉬난핑 중국 과학기술부 부부장(차관)은 29일 CCTV와의 인터뷰에서 “생식 목적의 인간 배아 유전자 교정은 중국에서 금지돼 있다”며 “법규도 위반했고, 과학계의 윤리 마지노선을 깨버린 놀라운 일”이라며 “객관적 조사를 기초로 법에 따라 조사, 처리하겠다”고 밝혔다. 쉬 본부장은 허 교수의 연구 활동도 중단시킬 것을 요구했다.

29일, 김진수 기초과학연구원(IBS) 유전체교정연구단장을 포함해, 이번에 허 교수가 참석했던 학회의 조직위원회도 공동성명을 발표했다. 위원회에는 “매우 불온한 주장을 이번 학회에서 들었다”며 “주장을 독립적으로 검증할 것을 추천하며, 설사 검증이 되더라도 절차가 무책임한데다 국제적 규범을 지키지 못해 흠결을 지니고 있다”고 밝혔다. 위원회는 “그 흠결은 의학적 절차, 잘못 설계된 연구 절차, 연구 피실험자의 후생을 보호하기 위한 윤리 기준 미충족, 임상 전 과정의 불투명성 등을 포함하고 있다”고 비판했다.

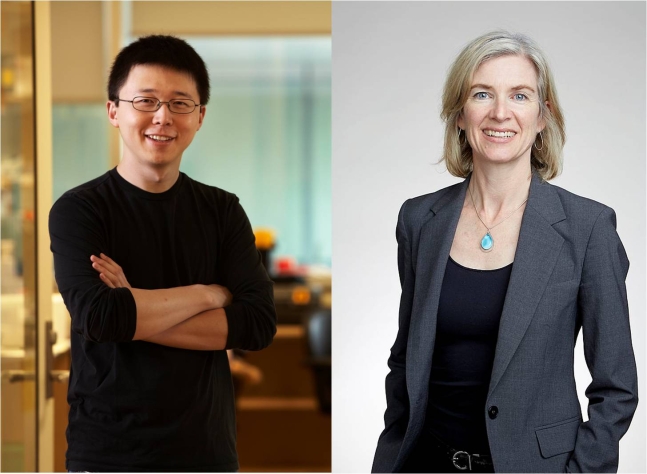

크리스퍼를 확립시킨 두 석학, 장펑 미국 브로드연구소 교수(왼쪽)과 제니퍼 다우드나 미국 캘리포니아대 교수. 두 사람 모두 각각 이번 사태에 비판적인 입장을 전했다.

법과 윤리를 떠나서, 이번 연구 자체에도 의문이 많다는 지적도 많다.이번 홍콩 학회에서 허 교수의 발표를 들은 김진수 단장은 30일 자신의 페이스북에 “왜 이렇게 무모하고 무책임한 선택을 했는지 의문”이라며 “이번 실험으로 태어난 쌍둥이 중 한 명인 ‘루루’는 CCR5 유전자가 없이 태어났고, 또다른 아기 ‘나나’는 한 쌍의 CCR5 유전자 중 하나는 그대로, 나머지 하나는 일부(15개 염기서열)가 결여된 변이 유전자를 갖고 태어났다”고 밝혔다.

특히 나나의 변이 유전자는 (15개 염기서열 결여에 따른) 5개 아미노산이 사라진 변이 CCR5를 지니고 태어났는데, 이 변이 CCR5 단백질이 특히 큰 우려를 자아내고 있다. 자연에 존재하지 않은 변이기 때문이다. 에이즈를 일으키는 HIV를 피할 수 있을지 미지수인 것은 물론이고, 예측 못한 다른 형질을 보일 수도 있다. 예를 들어 새로운 바이러스 감염을 돕는 역할을 할지, 다른 병을 유발할지 아무도 모른다. 잠재적인 위험에 대한 불확실성이 너무나 크다.

이완 버니 유럽생명정보학연구소(EMBL–EBI) 소장도 관련 보도가 처음 나온 미국 과학기술 잡지 ‘MIT 테크놀로지 리뷰’와 AP통신의 뉴스가 보도된 직후, 자신의 홈페이지에서 “이미 수십 년 전부터 시험관 아기를 태어나게 할 때 착상 전에 하는 유전진단(PGD)으로 충분히 이상이 없는 수정란을 고를 수 있다”며 연구 목적에 의문을 표했다. 버니 소장은 “수많은 동물 배아 연구를 통해 크리스퍼의 안전성을 더 할게 된 뒤에야 이 기술을 어떻게 책임감있게 사용할 수 있을지 알게 될 것”이라며 “이는 많은 연구와 규제가 필요한 일이며, 필요하다면 인간 배아에 대한 크리스퍼 이용을 결정하기 전까지 받아들일 만한 규제를 고려해 보는 것도 필요하다”고 말했다.

조지 처치 미국 하버드대 교수. -사진 제공 MaynardClark(W)

이런 가운데, 게놈 분야의 세계적 석학 중 하나인 조지 처치 미국 하버드대 교수가 부분적으로 허 교수를 옹호하고 나섰다. 처치 교수는 28일 과학잡지 겸 학술지 ‘사이언스’와의 인터뷰에서 “(일방적 주장 말고) 균형을 갖고 접근해야 한다”며 “연구에 대한 서류 작업이 제대로 이뤄지지 않은 점은 문제지만 서류 처리를 못한 사람이 허 교수가 처음은 아니다.”고 말했다. 허 교수의 연구에 의학적 성과가 아주 없지는 않다고 취지다.

그는 “분명 의학적으로 영향을 미치는 모자이시즘(한 개체에 둘 이상의 유전자형이 섞이는 현상)과, 의도하지 않은 부분을 수정하는 오류인 ‘오프타깃(off target)’ 현상이 분명 나타날 것이다”라며 “(하지만) 우리가 방사선의 영향이 0이 되길 기다렸다가 PET나 X선 촬영을 하는 것은 아니지 않는가?”라고 반문했다. 그는 “수십 마리 돼지와 쥐를 대상으로 실험했고 오프타깃 현상이 동물이나 세포에 문제를 일으켰다는 증거는 없었다”고 덧붙였다. 허 교수가 연구 과정이 불투명했고 과학계에 연구 의도를 좀더 분명히 밝혔어야 했다는 비판에 대해서는 “정당한 비판”이라면서도 “아기의 건강에 대해 좀더 초점을 맞춰야 한다”며 역시 유보적인 입장을 표했다.

원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~

First CRISPR babies: six questions that remain

Startling human-genome editing claim leaves many open questions, from He Jiankui’s next move to the future of the field.

The CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool is loaded into a pipette. Credit: Mark Schiefelbein/AP/Shutterstock

The meeting at which He Jiankui explained his extraordinary claim to have helped produce the first babies — twin girls — born with edited genomes came to a close with a statement that came down hard on the scientist.

“We heard an unexpected and deeply disturbing claim that human embryos had been edited and implanted, resulting in a pregnancy and the birth of twins,” reads the statement released by the organizing committee of the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong on 29 November. “Even if the modifications are verified, the procedure was irresponsible and failed to conform with international norms.”

Similar criticism has rained down since the revelation earlier this weekthat He had used the CRISPR–Cas9 genome-editing technique to modify the CCR5 gene in two embryos, which he then implanted in a woman. The gene encodes a protein that some common strains of HIV use to infect immune cells.

As researchers take stock of the week’s events, Nature summarizes six big questions that are still unanswered.

1. Is He Jiankui in trouble?

On 27 November, a day before He gave his talk at the summit, China’s national health ministry called on the government of Guangdong — where He’s university, the Southern University of Science and Technology is — to investigate He. Two days later, the science ministry ordered him to stop doing any science; He had already said the experiments were on hold. How the Guangdong investigation will proceed is not clear. He is accused of transgressing a 2003 health-ministry guideline, which is not a law and has no clear penalties attached to it.

Whether He’s university will take any action against him is also unclear. A university spokesperson told Nature that he “cannot disclose such information at this moment” and to wait for official statements “at an appropriate time.” He has been on leave since February 2018 and this is scheduled to last until January 2021; this week, the university criticized his claims and distanced itself from his work.

On 27 November, the laboratory web page hosted by the university — to which He has been referring people for information about the gene-edited babies — went down, although another site for He’s lab remains. Several statements praising He Jiankui’s accomplishments have also disappeared from government sites. A post on the science ministry’s site describing a genomic-sequencing technology that He developed, and a post praising He’s genomic sequencing technology on the website of the Thousand Talents Plan — a prestigious scheme to bring leading academics back to China — are both now inaccessible. It’s not clear if these actions are related to the week’s events, but both posts were still accessible until recently.

He went back to Shenzhen, where he lives, after his talk at the summit, according to a statement provided by He’s spokesperson, Ryan Ferrell, and missed a planned appearance at the summit on 29 November. “I have returned to Shenzhen and will not attend the conference on Thursday. I will remain in China, my home country, and cooperate fully with all inquiries about my work,” the statement said.

2. Are He’s claims accurate?

Many scientists have said that an independent body should confirm He’s scientific claims by performing an in-depth comparison of the parents’ and children’s genes. The problem is, almost everyone agrees that the babies and their parents should remain anonymous.

“He has kept them secret, and for good reasons,” says Nobel-prizewinning biologist David Baltimore, chair of the summit’s organizing committee and former president of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “We haven’t even laid out how that independent investigation will happen.”

He’s team could supply anonymized samples. Outside scientists could also visit He’s laboratory to analyse the data. In a statement released by his spokesperson, He said that he will invite other researchers to do an independent investigation. “My raw data will be made available for third-party review.”

He also says that he has submitted studies on his human gene-editing research to journals for publication. He has told some scientists that a paper will be published by the end of the year, but has not specified in which journal. But even if this happens, strict Chinese genetic-resources laws would prevent He from publishing the gene sequences of the parents or the children, and without those, scientists would have a difficult time verifying his claims.

3. How exactly did CRISPR edit the twins’ genomes?

In the absence of a peer-reviewed publication or preprint describing He’s gene-editing work, some scientists are parsing his presentation to try and understand how the twins’ genomes were edited — and any potential consequences of these changes.

Gaetan Burgio, a geneticist at Australia National University in Canberra who works on CRISPR gene editing, says that the raw sequencing data that He presented in his talk suggests that the babies’ cells harbour multiple edited versions of the CCR5 gene, with different-sized DNA deletions. Such ‘mosaicism’ can be caused when CRISPR edits some early embryo cells differently to others, or fails to edit some. Other researchers have reported mosaicism in efforts to edit human embryos for research purposes.

RNA researcher Sean Ryder, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, pointed out additional concerns in a Twitter post.

He Jiankui told the gene-editing conference that he targeted the CCR5gene because some people naturally carry a mutation in CCR5 — a 32-DNA-letter deletion known as delta-32 — that inactivates the gene. But Ryder says that that the CCR5 deletions that He claimed to introduce into the babies’ cells by CRISPR gene editing are not identical to the delta-32 mutation. “The point is that none of the three match the well-studied delta 32 mutation, and as far as I can tell, none have been studied in animal models. Unconscionable,” Ryder wrote in the post.

He Jiankui claims to have helped produce the first babies born with edited genomes.Credit: TPG via Zuma

4. When will there be another gene-edited human?

As Jennifer Doudna, a pioneer of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing tool, listened to He present his work at the summit, one idea kept coming back to her. “The thought I kept having was the potential for rogue scientists to use this in unethical ways. It’s a real risk,” says Doudna, a biochemist at the University of California, Berkeley,

Before He’s revelations, many scientists were already worried about the prospect that someone was on the brink of creating a gene-edited person. Biologist George Daley, dean of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and a member of the summit’s organizing committee, pointed to a procedure that replaces diseased mitochondrial DNA in an embryo with healthy mitochondrial DNA from another person, eliminating the embryo’s original disease-causing mutation. Although mitochondrial-replacement therapy lacks the approval of the biomedical community or the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), doctors based in New York City used it to produce a baby in Mexico in 2016. “Similar premature practice of embryo editing by CRISPR-Cas9 is likely despite our calls for caution,” Daley said.

At the Hong Kong summit, scientists discussed whether another announcement of human-germline editing — the modification of genes passed on to future generations — is nigh. “We do have reason to be concerned,” said Baltimore. “If anyone working in the field gets indications that it is happening, it is important they let authorities know.”

5. Will He’s revelations hamper ethical efforts to do germline editing?

Many researchers fear that He’s revelations could hamper the future of germline editing. “In the US some are suggesting draconian bans, which is antithetical to goals of science,” says Baltimore.

In the wake of the revelations, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb made comments that raised concerns among scientists. “Governments will now have to react,” he told the news site BioCentury. And on 28 November, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) director Francis Collins said in a statement that “the need for development of binding international consensus on setting limits for this kind of research, now being debated in Hong Kong, has never been more apparent.”

The statement released at the summit’s close makes a plea to keep open a path for safely translating gene-editing technology into treatments: “Germline genome editing could become acceptable in the future if these risks are addressed.”

But the debacle has focused worldwide interest on germline genome editing and fears of a chilling effect may be overstated. “There might be some women excited by the possibility of taking part in this research,” said Judith Daar, at the University of California Irvine School of Medicine and School of Law, at a summit satellite session when asked whether the controversy might dissuade women from donating eggs for research in the future. “The instinct is to say this is a debacle and could suppress participation. But I’m always amazed by the diverse reactions,” she added.

6. How will scientists ensure better oversight of germline editing in future?

“We don’t have a blueprint, but we have been asking academies,” said Baltimore. “It is a challenge to the world.”

The statement released by the summit’s organizing committee suggests that science academies around the world make recommendations to their own governments, while coordinating with each other.

It also suggests the creation of an international forum that would funnel research and clinical trials through an international registry, and discuss issues such as equitable access to the benefits of gene editing. But genome editing in human embryos potentially has an unwieldy range of users, and that could make maintaining such an organization difficult. “Virtually every lab doing molecular biology is using this technique,” said Daley.

The committee also suggested the need for a “translational pathway” that would provide a rigorous and responsible way for researchers to take germline gene editing to the clinic. Organizing-committee member Alta Charo, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin Law School in Madison, said expectations have to be realistic. “You can’t expect perfection. What you can do is try to minimize these incidents with enforcements that punish rogue behaviour.”

The next human genome-editing summit will take place in London in 2021.

원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~

첫번째 유전자 교정 아기 출산 : 법적·윤리적 문제에 대한 고찰

[요약]중국의 한 과학자가 배아의 유전자를 교정한 뒤 이를 자궁에 착상시켜 쌍둥이를 태어나게 하는데 성공해 논란이 되고 있다. 스탠퍼드대 법학과 교수이자 생명윤리 전문가인 행크 그릴리 교수는 “이번 시술은 불법이며 또한 두 아이가 안전하다고 담보할 수 없는 상황”이라고 지적했다. (2018.12)

지난달 중국남방대 과학자 허젠쿠이는 세계 최초로 유전자를 교정한 아기가 태어났다고 밝혔다. 이 아기는 에이즈를 유발하는 ‘인간면역결핍바이러스(HIV)’ 감염 위험을 줄이도록 DNA가 교정됐다. 허젠쿠이의 주장은 아직 확인되지 않았다. 중국 당국은 조사에 착수했고 관련 연구를 중지하라고 밝혔다. 이어지는 토론에서 미국 스탠퍼드대 법학과에서 새로운 생명의료 기술의 윤리학, 법학 및 회적 의미에 대해 연구하는 행크 그릴리 교수는 유전자 교정을 둘러싼 윤리적인 문제에 대해서 이야기한다.

◆ 먼저 중국 허젠쿠이 박사가 한 일을 설명해주세요

나는 그가 했다고 한 일에 대해서 설명할 수 있다. 하지만 허젠쿠이 박사가 유투브를 통해서 이야기한 것 말고는 어떤 일을 했는지 모르겠다. 그가 유전자를 교정했다는 것과 함께 유전자가 교정된 아기가 존재한다는 독립적인 증거는 아직 없다. 이것은 대단한 사기일 수 있다. 이같은 대담한 사기는 과거 2004~2005년 황우석 박사가 인간 배아줄기세포 복제에 성공했다고 발표한 거짓 주장 등 생명과학분야에서 있어왔다.

그가 말한 것이 실제로 이뤄졌다고 가정하면, 허젠쿠이 박사는 ‘크리스퍼 카스9’이라 불리는 환상적인 유전자 교정 도구를 인간 난자가 수정된 직후, 배아에 사용했다. 그의 목표는 CCR5라고 불리는 유전자를 바꾸는 것이다. 이 유전자는 백혈구 바깥쪽에 있는 단백질을 만든다. 이 단백질은 면역시스템에서 중요한 역할을 차지하는데 이를 T세포라고 부른다. CCR5가 결핍된 T세포는 HIV에 감염되지 않는다는(혹은 거의 감염되지 않는다는) 여러 증거가 있다. 북유럽 사람들의 약 1%는(그밖에 소수의 사람들이) CCR5에 작은 변화가 있어 HIV에 감염되지 않는 것으로 알려져 있다. 따라서 그의 목표는 HIV에 감염에 면역력이 있는 배아를(그리고 아기들, 10대들, 성인들) 제공하는 것이었다. 하지만 그가 발표한 자료는 쌍둥이 중 한 명은 세포의 절반만 수정됐다. 만약 그녀의 세포 중 절반이 CCR5를 가지고 있다면 그녀는 여전히 HIV 감염에 취약하다. 쌍둥이 중 다른 한명은 모든 세포의 DNA가 변한 것으로 나타났지만 허젠쿠이 박사가 의도한 것은 아니었다. 우리는 여전히 그녀가 HIV감염으로부터 완벽하게, 또는 일부 저항할 수 있는 면역시스템을 갖췄는지 알 수 없다.

◆ 이것은 미국에서 합법인가? 그렇지 않다면 이유는 뭔가.

이것은 미국에서 합법이 아니다. 내 생각에 미국식품의약국(FDA)은 법원이 유지할 것으로 보이는 입장을 취할 것이다. 유전적으로 변형된 인간 배아는 약물이나 생물학적 제품이며 법원의 관할 아래 존재한다. 새로운 약을 FDA승인 없이 배포하는 것은 불법(연방범죄)에 해당한다. 연구목적으로 FDA 승인은 쉽게 받을 수 있다. 당신은 FDA에 ‘연구용 신약’ 면제를 위한 신청서를 제출해야 한다. 또한 당신은 FDA에 이 실험은 좋은 목적이며 실험 참가자들에게 위험하지 않으며 실험이 효과적일 것이라는 합리적인 증거를 제출해야만 한다. 허젠쿠이 박사의 이번 일은 어느쪽도 만족시키지 못했다. 따라서 연구용 신약 허가도 받지 못할 것이다. 그러나 2015년 12월 이후 의회는 정기적으로 FDA의 자금조달 법안에 개정안을 추가해 어떤 계열의 인간 생식세포에 대한 유전자 교정을 금지하고 있다. 따라서 만약 당신이 허젠쿠이 박사가 한 실험을 미국에서 했다면 FDA의 승인 없이 했을 것이고 신약을 불법적으로 유통시키는 것과 같은 상황이 된다. 다른 여러 나라에서도, 특히 유럽에서는 특정 법령에 의해 인간 생식계열 세포의 유전자를 교정하는 것은 불법이다. 이같은 법이 없는 나라에서는 합법일 수 있다(적어도 불법이 아닐 수 있다).

◆ 위험은 무엇인가? 잠재적인 이득은 무엇인가

아이들에게 있어서 크리스퍼 유전자 가위가 갖고 있는 위험성은 다른 부분의 DNA를 손상시킬 수 있다는 점이다. 이를 ‘오프 타겟 효과’라고 부른다. 이는 유전자 가위를 사용할 때 상당히 일반적으로 나타난다. 유전체의 다른 부분이 변하는 것과 함께 허젠쿠이 박사는 그가 목표로 했던 CCR 유전자를 정확하게 바꾸지 못했다. 또한 허젠쿠이가 수정한 유전자는 HIV를 막는데 효과적이지 않을수도 있고 해로울 수도 있다.

두번째 위험은 CCR5가 없는 유전자는 자신만의 문제를 갖고 있을 수 있다는 점이다. CCR5가 없는 북유럽 성인들은 겉으로 보기에는 건강해 보이지만 다른 문제가 있는지 면밀히 관찰된 적이 없다. 예를 들어 CCR5가 없을 경우 웨스트나일 바이러스나 인플루엔자에 취약할 수 있다는 증거도 나오고 있다.

아기에게 있어서 잠재적인 이익은 HIV에 대한 면역이지만 이것이 차지하고 있는 비중은 상당히 적다. 쌍둥이 중 한명은 CCR5가 완전히 제거되지 않아 HIV에 대한 면역능력이 없을 것이다. 또한 두 아이는 모두 HIV에 노출됐을 때 감염될 가능성을 조금이라도 갖고 있다. HIV는 이미 관리 가능한 질병이다. 20년 내에 그 질병을 얼마나 쉽게 예방할 수 있게 될지 알 수 없다.

과학·의학에서 얻을 수 있는 잠재적인 이득은 크리스퍼 유전자 가위로 유전자가 교정된 아기가 태어날 수 있다는 점이다. 하지만 이 기술이 성공할 가치가 있다면, 이것은 다른 대안이 없는 심각한 질병을 대상으로 진행되어야 하며 이번 일과는 전혀 다른 방향으로 진행됐어야 했다.

◆ 이것이 언제 합법화 될까

FDA가 이것을 진행할 수 있을 만큼 안전성이 확보됐다고 생각하면 진행될 수 있다. 하지만 난 이것이 곧 일어날 것이라고 보지 않는다.

◆ 이것은 국제기구에 의해서 통제 가능한가. 어떻게 규제되어야 하는가

미국에서는 FDA와 IRB에 의해 감독된다. 완벽하지는 않지만 그렇다고 끔찍한 것은 아니다.

◆ 합법화 되면 우리가 마주하게 될 윤리적 문제는 무엇인가

아이들의 안전 문제가 핵심이다. 그것 말고도 인간 유전학에 대한 인류의 지식에 비추어볼 때 배아의 유전자 교정이 배아 선택보다 낫다고 볼 수 있는 점은 거의 없다. 우리는 ‘슈퍼 아기’를 만들만큼 많은 것을 알지 못하고 조만간 이런 일이 발생할 것 같지도 않다. 미래 세대로 전해질 수 있는 유전자 교정, 편집이 어떤 사람들에게는 정말 큰 윤리적인 문제가 될 것이다. 이것은 ‘기준선’이다. 우리는 이를 넘어가면 안된다.

◆ 어떤 법적 문제를 예상하나

만약 이것을 합법화되기 전에 시도한다면 임상의학, 과학자들에게 연방범죄 혐의가 예상된다. 유전자가 변형된 인간 배아가 FDA법상 신약인지, 의료기기인지에 대한 의문이 생길 수 있다. 만약 이것이 합법이 되고 난 뒤 시행했는데 잘못됐다면 큰 의료과실 소송으로 이어질 수 있다.

**허젠쿠이 박사는 스탠퍼드대 스테판 퀘이크 교수 연구실에서 2011~2012년 박사후연구원으로 있었다. 퀘이크 교수 연구실에서 허젠쿠이 박사는 컴퓨터 분석과 관련된 연구를 했으며 이는 유전자 교정과 관련된 일은 아니었다.

(원문)

원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~

Geneticists retract study suggesting first CRISPR babies might die early

Researchers rapidly corrected finding through discussions on social media and preprints.

Errors in techniques for tracking down genetic mutations led to erroneous results in a now-retracted study.Credit: Getty

A study that raised questions over the future health of the world’s first gene-edited babies has been retracted because of key errors that undermined its conclusion.

The research, published in June 2019 in Nature Medicine1, had suggested that people with two copies of a natural genetic mutation that confers HIV resistance are at an increased risk of dying earlier than other people. It was conducted in the wake of controversial experiments by the Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who had attempted to recreate the effects of this mutation in the gene CCR5 by using the CRISPR gene-editing tool in human embryos. The twin girls born last year as a result of the work did not end up carrying this exact mutation, but the research attracted attention because of its potential relevance to such experiments.

But a flurry of studies2,3,4 that looked anew the Nature Medicine research — some of which analysed new data from genome databases comprising sequences from hundreds of thousands of people — have rejected the results and find no evidence that people with the mutation die early. The erroneous conclusion about CCR5 was caused by technical errors in how the mutation was identified in a population-health database.

“I feel I have a responsibility to put the record straight for the public,” says Rasmus Nielsen, a population geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley, who led study, which the authors retracted on 8 October. Nielsen also co-authored one of the papers rebutting its findings.

Some researchers stress that because the twins did not receive exactly the same mutation that occurs naturally, the original research and its retraction would not necessarily offer insights into their health anyway. But the episode raises questions about how best to assess the safety of future attempts to edit genes in human embryos.

CRISPR concern

He Jiankui shocked the scientific world when he announced, in November 2018, that his team had used CRISPR to disable the CCR5 gene in two babies born that month. He, who was at the time a biophysicist at the Southern University of China in Shenzhen, said he chose to target CCR5 because people with a 32-DNA letter deletion known as delta-32 in the gene are resistant to HIV but seem not to experience significant related health problems.

He has not published data supporting his work, but his announcement — presented at a scientific meeting — indicated that, for one of the twins, both copies of CCR5 were altered, whereas the other twin carried edits in just one of her two copies. None of the changes exactly matched the delta-32 variation.

Research has hinted that the delta-32 mutation, which is relatively common in people of European ancestry, might carry downsides — one small study5 found that carriers were more likely than other people to die from influenza. To tackle the question in larger data sets, Nielsen and his Berkeley colleague Xinzhu Wei looked at the UK Biobank, a database containing genome and health data from 500,000 British people.

Their Nature Medicine paper1 reported that people with two copies of delta-32 — whom they estimated to make up about 1% of biobank participants — were slightly more likely to die by the age of 76 than were those with one or no copies. They also found that the database harboured fewer people with two copies of delta-32 than evolutionary theory predicted it should — a sign that individuals with two copies were dying earlier, on average, than the population at large, Wei and Nielsen argued.

Results not replicated

Questions over the conclusion emerged as soon as the paper was published. Sean Harrison, an epidemiologist at the University of Bristol, UK, attempted to replicate the findings that night. He did not have UK Biobank data on the gene variant that Wei and Nielsen used to identify carriers of delta-32, so he analysed genetic variants near it on the genome that should have given the same result (adjacent parts of the genome tend to be inherited together, allowing scientists to infer the presence or absence of a DNA sequence by analysing neighbouring variants). When they didn’t, he described his findings in a series of tweets and later a blogpost.

The discrepancy Harrison identified piqued the interest of David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, whose lab is studying CCR5. Working with Nielsen, his team discovered2 that Neilsen and Wei’s method had caused them to undercount the number of people in the UK Biobank with two copies of the delta-32 mutation, because the probe that measured the variant they were tracking did not always identify its target sequence. This — and not the supposed harmful effects of the mutation — explained the apparent absence of carriers from the UK Biobank database, says Nielsen.

He stresses that the undercounting problem is unique to the gene variant his team looked at, and not a general issue with UK Biobank data. “There were checks we could have done and should have done that we didn’t do. We missed the fact that there was a genotyping error,” Nielsen says.

Another follow-up study3, posted on a preprint server last week and based on genome databases that together include nearly 300,000 people from Iceland and Finland, also found no evidence that people with two copies of delta-32 die earlier than others.

No green light

Researchers stress that the unravelling of Wei and Nielsen’s results does not mean that it is a sound idea to target CCR5 for gene editing. “It’s very reasonable to expect that it might have a valuable function that we just don’t know how to measure. It seems very unwise to edit it out,” says Reich.

Gaétan Burgio, a geneticist at the Australian National University in Canberra, says the original Nature Medicine paper offered no insights into the health of the gene-edited twins. “Therefore, the retraction and these additional studies on European populations will still have no relevance to CRISPR babies, in my view,” he says. Population-based studies are very unlikely to give insights on these two babies, who don’t carry the CCR5-delta-32 mutation, he says.

Nielsen hopes that his team’s error does not dissuade others from using databases such as the UK Biobank to understand the effects of editing the human germ line, the DNA that can be passed on to future generations.

Kári Stefánson, head of the company deCODE genetics in Reykjavik and a co-author of one of the papers that found no evidence that delta-32 is harmful, says that Nielsen’s original study was not a valuable contribution to debates over germline gene editing. But he agrees that resources such as the UK Biobank and his company’s data on Iceland’s population can inform future efforts. “I think databases like this provide a fairly good way of assessing the probable effect of altering bases, no question about it,” he says.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)