1869년 11월 4일 1호 발간

7일 150주년 기념 생방송

1986년 11월 4일 발간된 과학저널 `네이처` 1호의 표지. [사진 제공 = 네이처]

세계적인 과학저널 ‘네이처’가 창간 150주년을 맞았다. 네이처는 4일(현지 시간) 150주년을 기념해 홈페이지에 그동안 네이처를 통해 발표된 다양한 분야의 연구 결과 중 세계 과학계의 과거와 현재, 미래를 엿볼 수 있는 대표적인 성과들을 소개했다. 네이처는 이날 “네이처의 첫 호는 1869년 11월 4일 발간됐다”며 “네이처의 역사는 지난 150년간 과학과 사회가 어떻게 변모해왔는지 보여 준다”고 밝혔다.

인류와 기원과 진화 역사에 가까이 다가간 연구 결과가 대표적이다. 1925년 호주의 고고학자인 레이몬트 다트는 아프리카에서 이전까지 알려져 있지 않았던 인류 종인 ‘오스트랄로 피테쿠스’의 화석을 발견했다고 네이처에 발표했다. 이 발견은 인류의 초기 진화에 대한 이해를 혁명적으로 변화시켰다. 실제로 이후 아프리카에서는 100만 건에 이르는 다양한 오스트랄로 피테쿠스의 화석 표본이 발견됐다.

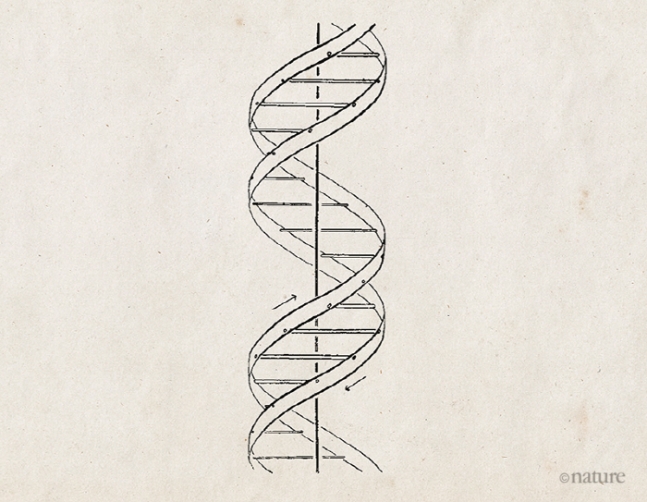

인체의 비밀을 밝힌 연구도 눈에 띈다. 1953년 제임스 왓슨과 프랜시스 크릭은 유전 정보를 다음 세대로 전달하는 물질인 DNA의 구조가 이중나선형이라는 내용의 논문을 DNA 구조를 그린 한 장의 그림과 함께 발표했다. 이로부터 9년 뒤 이들은 생물학계의 가장 중요한 수수께끼를 푼 공로를 인정받아 DNA의 구조를 밝히는데 기여한 또 다른 과학자 모리스 윌킨스와 함께 노벨 생리의학상을 수상했다.

1953년 영국의 생물학자 제임스 왓슨과 프랜시스 크릭이 처음 제안한 DNA의 이중나선 구조. [사진 제공 = 네이처]

1958년 존 고든은 한번 분화된 세포를 다시 분화 전 상태로 되돌릴 수 있다는 것을 발견해 네이처에 발표했다. 아프리카 개구리의 세포를 재프로그래밍해 분화 이전 단계로 옮겨 올챙이의 세포로 만드는 데 성공했다. 이전까지는 분화는 돌이킬 수 없는 것으로 알려져 있었지만, 이들의 발견은 오늘날 ‘유도만능줄기(iPS)세포’를 비롯한 세포 재프로그래밍 분야의 기초를 닦았다. iPS세포는 피부 세포를 역분화시켜 배아줄기세포처럼 모든 종류의 세포로 분화할 수 있는 상태로 만든 줄기세포로, 각종 난치성 질환 치료와 이식용 장기 연구 등에 활용되고 있다.

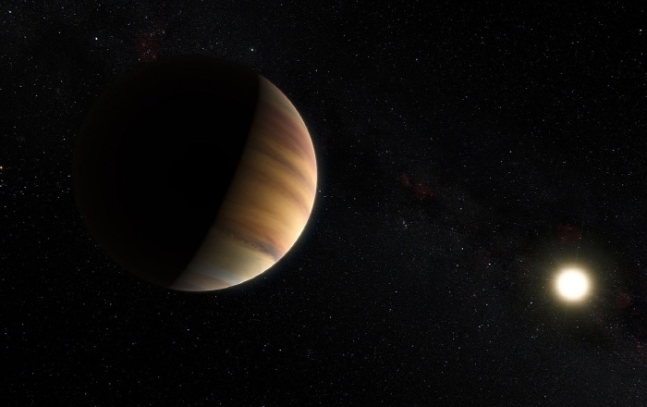

네이처는 천문학계의 무대가 되기도 했다. 1995년 사제 지간인 미셸 마요르 스위스 제네바대 명예교수와 당시 대학원생이었던 디디에 쿠엘로 제네바대 명예교수는 프랑스 남부 천문대의 망원경을 이용해 태양계 외부에 있는 항성(별)의 밝기가 변하는 것을 관측해 최초로 태양과 같은 종류의 별(주계열성) 주변을 돌고 있는 외계행성을 발견했다. 이들이 발견한 행성은 지구로부터 50광년(1광년은 빛이 1년 동안 이동하는 거리·1광년은 약 9조4000억㎞) 떨어진 페가수스자리의 51번째 별을 공전하고 있는 가스형 행성으로 ‘페가수스 51b’라는 이름이 붙었다. 이들의 관측으로 태양계 밖에도 태양계 행성과 유사한 행성들이 무수히 많이 존재한다는 사실이 밝혀졌다.

올해 노벨 물리학상을 수상한 스위스 제네바대의 미셸 마요르 명예교수와 디디에 쿠엘로 교수가 1995년 발견한 `페가수스 51b`의 상상도. 이 행성은 태양계 밖에서 태양과 같은 유형의 별(주계열성) 주위를 공전하는 행성 중 최초로 발견했다. [사진 제공 = 유럽남방천문대]

소재 분야에서의 혁명적인 발견도 있었다. 1985년 미국 라이스대 연구진은 탄소 원자 60개가 육각형 20개와 오각형 12개로 이뤄진 축구공 모양으로 연결된 형태의 탄소 분자 ‘풀러렌(C60)’을 발견해 네이처에 발표했다. 이 분자는 향후 그래핀, 탄소나노튜브 같은 신소재와 나노 기술의 토대가 됐다. 버크민스터풀러렌을 발견한 해럴드 크로토와 로버트 컬, 리처드 스몰리 등 3인의 과학자는 1996년 노벨 화학상을 수상하기도 했다.

1992년에는 오늘날 수많은 다공성 물질의 합성을 가능케 한 화학반응 원리가 네이처에 발표됐다. 당시 크레스기 레오노비치는 다공성 물질의 합성을 위한 주형으로서 ‘미셸’이라고 불리는 원통형 분자 응집체를 사용할 수 있음을 밝혔다. 이 연구는 다공성 물질 연구를 폭발적으로 발전시켰다. 직경이 2㎚(나노미터·1㎚는 10억분의 1m) 미만인 균일한 기공을 갖는 결정성 규산화 알루미늄 화합물인 ‘제올라이트’ 등 다공성 물질은 오랜 기간 석유 정제를 위한 촉매로 사용돼 왔고, 현재는 약물 전달체 등 의생명 분야에서도 다양한 다공성 물질을 응용하고 있다.

그 밖에 네이처는 기억을 삭제하거나 편집하는 기술의 발전사를 비롯해 남극 상공의 오존층 구멍 발견, 아인슈타인이 예측한 중력파 발견과 다중신호 천문학 시대의 개막, 후천적인 유전자 변화를 추적하는 후성 유전학의 진보, 기후변화 예측, 노화 연구의 발전, 유기 합성의 디지털화 등을 소개했다. 네이처는 오는 6일 오후 6시(한국시간 7일 새벽 3시) 150주년을 기념하는 라이브 방송을 할 예정이다.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

Nature at 150: evidence in pursuit of truth

A century and a half has seen momentous changes in science. But evidence and transparency are more important than ever before.

Nature made its debut on 4 November 1869.

On 4 November 1869, the first issue of Nature made its way into the world. Its ambition was intellectually bold and commercially risky: to bring news of the latest discoveries and inventions to scientists and the public alike.

Although the journal was aimed at a broad audience, scientists took a particular liking to it — because it allowed them to communicate their findings quickly. Nature’s weekly schedule offered a refreshing contrast to the leisurely timescales of learned-society journal publishing and conference proceedings. And, as universities grew, more ‘letters to the editor’ from scientists started arriving at the Nature offices in London. The journal became a venue for publishing discoveries because its writers also became its readers — and we have been trying to serve scientists and society ever since.

In this, Nature’s 150th anniversary issue, we’re celebrating and remembering many of the notable discoveries that authors have communicated in the journal’s pages, along with the agenda-setting journalism and commentary that has always been an essential part of our voice.

A century and a half is long enough to see how our understanding of the natural world changes with each instalment of new evidence. Take human origins. In February 1925, Nature published the discovery by Raymond Dart of Australopithecus africanus in South Africa1. It was the first fossil link between humans and apes, and it caused a sensation, providing evidence that humans evolved from a common ancestor in Africa as Charles Darwin had proposed — and not in Britain or Indonesia as had previously been thought.

Nearly 80 years later, the discovery of the remains of Homo floresiensis in 2004, which came to be known as the hobbit, demonstrated that our genus was remarkably diverse2. Further revelations about human prehistory and evolution quickly followed, culminating in advances in ancient genomics. These have revealed that, as recently as 30,000 to 60,000 years ago, humans coexisted and had offspring with other hominins — Neanderthals and Denisovans3.

Nature also published some of the remarkable developments that took place in physics in the early part of the twentieth century. These include James Chadwick’s proposal in 1932 of the existence of a new particle, the neutron, to add to the electron and the proton4. Today, many more fundamental particles have been discovered because of the predictions of the standard model of particle physics. Some of the earliest findings of exoplanets appeared in our pages, including, in 1995, the first report of an exoplanet orbiting around a Sun-like star in another galaxy5 — for which Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz won a share of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Arguably, Nature’s most memorable publications were the reports in April 1953 on the structure of DNA — including papers from Maurice Wilkins6 and Rosalind Franklin7, in addition to the paper by Francis Crick and James Watson8. The discovery that DNA was a double helix changed biology forever. Forty years later, we proudly published the first draft sequence of a human genome carried out by a publicly funded group, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium9. Without the researchers’ collective achievement, medicine, agriculture, conservation and criminal justice would look very different today.

There is, of course, no definitive list of the most influential or important pieces of research that Nature has published. A series of News & Views articles explains the importance and lasting impact of ten key papers from our archive. We also chose a long list of 150 interesting, illuminating, entertaining and sometimes controversial articles — one for every year of our life — and have been posting one per day on social media for the past few months. But even compiling this longer list involved vigorous and sometimes tense discussion among the editors.

At the start of the year, we also began discussing what to feature on our anniversary issue cover. The result — a data analysis of Nature’s archive which highlights the multidisciplinary scope of the journal — is rendered as the extraordinary fireworks you can see on the cover and in a video and interactive visualization. Our anniversary issue includes a rich variety of written and multimedia content on the past, present and future of Nature and of research itself.

Responsible science

As science has advanced during the past century and a half, discovery has gone hand in hand with world-changing inventions — particularly in industrial-scale technologies. Many of these technologies, from the internal combustion engine to synthetic agrochemicals, have improved the quality of life for hundreds of millions of people; but at the same time they have also damaged the environment or raised serious ethical and safety concerns.

In some cases, researchers have been able to sound the alarm in time for remedial action, as chemists Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland did in June 1974 when they worked out that chlorine originating from chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) was destroying atmospheric ozone10. A decade later, physicist Joe Farman and colleagues showed that ozone levels over Antarctica were lower than expected — the first detection of the ozone hole11.

These findings led to the 1989 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to cut ozone-depleting substances, and a shining example of how people can unite to take action when scientific evidence points to an impending environmental disaster. Sadly, the same cannot yet be said for climate change, even though researchers have been sounding ever-louder warnings since the 1970s that greenhouse-gas emissions are warming the planet.

As the pace of discovery and invention accelerates — from isolating stem cells12 to the development of cloning13 and gene-editing technologies, to last month’s description of quantum supremacy14 — there is a clear need, perhaps now more than ever, for researchers and research publishers to acknowledge, and implement, our responsibility to society. We must commit to greater openness and ensure that findings are reproducible, and we must act with integrity at all times. Nature and the researchers it serves have a duty to work side by side with those in our broader society who will be affected by the products of research, and to consider generations to come.

Room to improve

Looking back, there have been times when Nature did not adhere to standards that we hold ourselves to today. We should have called out when Jocelyn Bell Burnell was overlooked for the Nobel physics prize for her work in the discovery of pulsars15. And it shouldn’t have taken until 2007 for us to replace the phrase “scientific men” with “scientists” in our mission statement.

Organized peer review — the cornerstone of scientific publishing — was introduced in Nature only after 1966, although we have tried to make up for lost time since. In 2006, Nature conducted trials on open peer review; we now offer authors double-blind peer review, and are one of several journals in the Nature family to offer reviewers the opportunity to be named.

Another area where overdue change is under way is in the people represented in the journal. In the early years, Nature was dominated by papers with one or two authors, mostly male, and mostly from the Northern Hemisphere. Today, papers with a single author are almost unheard of and author lists can run to the thousands, reflecting the increasingly team-based nature of current research. Although most of our authors still come from institutions in Europe and North America — where most research funding is concentrated — our author community is becoming more geographically diverse.

But researchers from large parts of the world, notably Africa, remain under-represented. This reflects broader inequalities that stem from the uncomfortable historical reality that science and empire often worked in a symbiotic relationship. We recognize that Nature was founded at the height of such an age. Change will need time, but we are committed to doing more to make a difference.

View to the future

As the boundaries between disciplines blur and research becomes increasingly multi- and transdisciplinary, Nature is moving beyond a traditional focus on the natural sciences to embrace social sciences, translational and clinical research and applied science and engineering. Looking to the future, we hope to contribute to greater transparency and openness in academia. We will probably see even more collaborative ways of doing research and more changes in the way it is published.

Predicting the future is notoriously difficult. Writer William Gibson, in his 1984 cyberpunk novel Neuromancer, foresaw a form of today’s stem-cell therapy and sophisticated artificial intelligence, but failed to anticipate mobile phones. Even in the early 1990s, relatively few people anticipated that ‘electronic publishing’, as it was starting to be called, would jeopardize the future of mass-produced printed journals. The most exciting and dramatic changes will be the ones we cannot imagine today.

It’s unlikely that our founders imagined that, 150 years on, Nature would be publishing more than 850 research papers and 3,000 articles of news, opinion and analysis each year, and reaching around 4 million readers online each month. That’s your doing: researchers and their remarkable discoveries have made us what we are. We have reached this important milestone only through listening, responding and adapting to the community we serve.

In other respects, Nature now is just the same as it was at the start. We will continue in our mission to stand up for research, serve the global research community and communicate the results of science around the world. We will strive to hold to account those in positions of responsibility in research, policy and industry, and to continue to advocate for fewer unintended harmful consequences of research for people and the planet.

Research, science, knowledge, scholarship — however we might choose to characterize the marshalling of evidence in the pursuit of truth — the values we hold are more important than ever before.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)