(원문)

A redesigned yeast genome is being constructed to allow it to be extensively rearranged on demand. A suite of studies reveals the versatility of the genome-shuffling system, and shows how it could be used for biotechnology applications.

A global consortium of scientists is well on the way to making a synthetic genome for the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae1 — the first synthetic genome for a member of the group of organisms known as eukaryotes, which includes plants, animals and fungi. Embedded within the extensively redesigned ‘version 2.0’ genome of S. cerevisiae (Sc2.0) are DNA sequences that form part of a system known as Synthetic Chromosome Rearrangement and Modification by LoxP-mediated Evolution (SCRaMbLE). This system allows extensive reorganization of the genome to be triggered on demand, generating Sc2.0 variants that have diverse genetic make-ups and characteristics. Sc2.0 is therefore a versatile platform that can be easily modified and evolved to produce yeasts that have desired attributes2. A collection of seven papers3–9published in Nature Communications demonstrates the immense potential of Sc2.0 for engineering and understanding yeast.

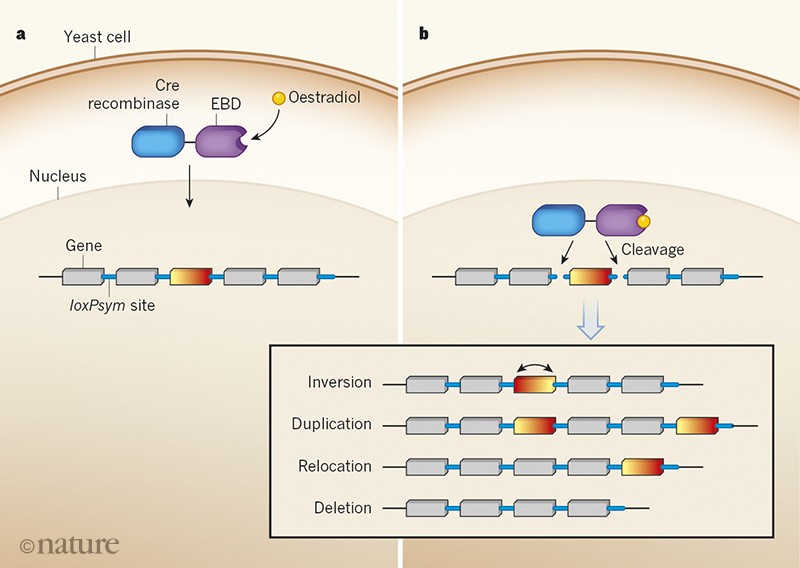

To enable SCRaMbLE, a palindromic DNA sequence known as loxPsym is inserted after every non-essential gene in the synthetic genome. In the presence of the enzyme Cre recombinase, the loxPsym sites undergo recombination with each other — that is, the loxPsym sequences break in the middle, and the broken ends can then join up with any other available loxPsym ends. This process results in genes being randomly deleted, inverted, relocated and duplicated.

In the original design of the SCRaMbLE system10, Cre recombinase was produced only once during the lifetime of a cell, and was fused to a protein domain that binds oestradiol molecules — which allowed the enzyme to be activated by adding oestradiol to the yeast’s growth medium, providing an on–off switch for genome rearrangement (Fig. 1). However, some ‘background’ genome rearrangement occurred even without oestradiol activation. This version of SCRaMbLE was functional11,12, but four of the new papers now report improvements to the system.

Figure 1 | Genome rearrangement on demand. A synthetic genome of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is being constructed that allows the genome to be rearranged using a system known as Synthetic Chromosome Rearrangement and Modification by LoxP-mediated Evolution (SCRaMbLE). In the first version of this system, a palindromic DNA sequence known as loxPsym is inserted after every non-essential gene, and a protein consisting of the enzyme Cre recombinase attached to an oestradiol-binding domain (EBD) resides in the yeast cytoplasm. When the protein is activated by the binding of an oestradiol molecule, it moves into the nucleus (a) where it cleaves the loxPsym sequences (b). The broken ends ofloxPsym can then join up with any other available loxPsym ends, rearranging the genome. This process results in genes (such as the coloured rectangle) being randomly inverted, duplicated, relocated or deleted. Seven papers3–9 now report improvements and applications of the SCRaMbLE system.

Shen et al.3 have modified SCRaMbLE to produce multiple pulses of Cre recombinase (instead of just one per lifetime) to increase rearrangement events while reducing background Cre recombinase activity. Jia et al.4have developed a SCRaMbLE variant in which both oestradiol and galactose molecules are required to activate rearrangement, also reducing background rearrangement. Hochrein et al.5 have engineered Cre recombinase so that it is activated by red light, providing a new way to control SCRaMbLE. And Luo et al.6 have introduced a reporter DNA sequence into a synthetic yeast strain, which allows cells that have undergone SCRaMbLE-induced genome rearrangement to be easily distinguished from those that have not. All four improvements facilitate effective and efficient implementation of SCRaMbLE.

An important application of SCRaMbLE is to generate genetically diverse pools of yeast mutants from which strains that have industrially valuable characteristics can be isolated. For example, yeasts can be genetically engineered to produce useful compounds, and Blount et al.7 show that SCRaMbLE can generate yeast strains that produce antibiotics (violacein or penicillin) in greater quantities than could be achieved without SCRaMbLE. Blount and colleagues also used the system to produce yeast strains that use the sugar xylose for growth more effectively than strains produced without SCRaMbLE; xylose is poorly used by wild-type yeast, but is abundant in biomass and is therefore an attractive alternative to the sugars normally used to feed yeast in industrial applications. And Luo et al. have used their SCRaMbLE variant to accelerate the isolation of yeast strains that are tolerant to various stress factors, such as ethanol, heat and acetic acid.

Jia and co-workers report that production of β-carotene molecules can be drastically increased if SCRaMbLE is used in diploid yeasts, which have two copies of the genome, instead of haploids, which have a single copy. Similarly, Shen et al. used SCRaMbLE in diploids to improve the heat or caffeine tolerance of hybrid yeasts (organisms produced by crossing two different yeast species or subspecies). Both groups observed genome rearrangements in diploids that involved the deletion of one copy of essential genes. The presence of such rearrangements in improved diploid strains shows that, compared to haploids, diploids are more robust to deleterious deletions during SCRaMbLE. This in turn allows a greater number of beneficial rearrangements to be manifested. Although it is premature to claim that SCRaMbLE is a universal tool for engineering yeast, taken together, the various findings3–7 certainly show that it has great potential for generating yeasts for a wide range of purposes.

Wu et al.8 have taken SCRaMbLE out of cells and used it in vitro with purified Cre recombinase to generate different genetic arrangements of the β-carotene biosynthetic pathway. They thus discovered arrangements that increase β-carotene production compared with the original pathway. By contrast, Liu et al.9 used an in vitro method involving recombinase enzymes separate from the SCRaMbLE system, to rapidly generate different versions of β-carotene- and violacein-producing pathways and to identify highly productive ones. They then flanked the DNA sequences of the best pathways with loxPsym, and used SCRaMbLE to randomly incorporate the pathways at loxPsym sites in the synthetic yeast genome. SCRaMbLE concurrently rearranged the resulting genomes, allowing yeast strains to be optimized for the production of the desired compounds. These two papers illustrate the versatility of the basic SCRaMbLE concept and how it can be used in innovative ways.

So where next for Sc 2.0? So far, six synthetic chromosomes of Sc2.0 have been completed13, and consortium members are working full-time to construct the remaining ten. The seven new papers show that researchers are eager to work with the newly available synthetic chromosomes to see how SCRaMbLE techniques can generate useful yeast variants and improve our understanding of the fundamental processes and properties of yeast. Thousands of loxPsym sites will be present in the fully assembled Sc 2.0 genome, and so the number of genomic structures that can be generated by SCRaMbLE is immense — which suggests that it should be possible to produce a yeast variant that displays any desired set of characteristics.

Nevertheless, SCRaMbLE systems are still in their infancy. Further improvements are needed, along with tools that maximize the potential of SCRaMbLE-based techniques. For example, the screening of SCRaMbLE-modified yeast has generally relied on visible cues, such as growth rate and colour (both β-carotene and violacein are pigments that colour the yeast cells). Luo and colleagues’ reporter offers a useful new screening tool, but high-throughput methods are also needed that can identify yeast strains that produce large amounts of colourless chemicals. Crucially, the characterization of genetic rearrangements relies heavily on whole-genome sequencing. The development of more-efficient, cheaper sequencing techniques would allow more strains to be sequenced than is currently possible, to work out and study changes in the genome. Given the promising early results and synergy among the members of the Sc2.0 consortium, the establishment of SCRaMbLE as a staple tool for engineering yeast is highly anticipated.