By expanding the scope of sustainability to the entire lifecycle of chemical products, the concept of circular chemistry aims to replace today’s linear ‘take–make–dispose’ approach with circular processes. This will optimize resource efficiency across chemical value chains and enable a closed-loop, waste-free chemical industry.

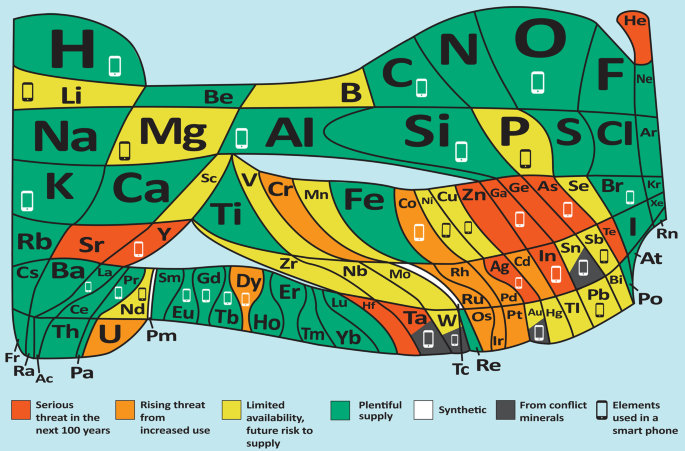

Awareness of the finite nature of many resources — including the issue of element scarcity, shown in Fig. 1 — as well as the limited environmental tolerance towards our chemical industry has grown tremendously in the past few decades. It has become painfully obvious that the linear route of production, in which scarce resources are consumed and their value-added products are degraded to waste, is a route cause of several impending global crises such as climate change, diminished biodiversity, as well as food, water and energy shortages.

© EuChemS, reproduced from https://www.euchems.eu/euchems-periodic-table/ under a Creative Commons license CC BY-ND 4.0

In this representation of the periodic table prepared by the European Chemical Society (EuChemS) for the International Year of the Periodic Table, naturally occurring elements (except some of the rarest ones beyond uranium53) are depicted through tiles, the size of which gives an indication — on a logarithmic scale — of how much of the element is present in the Earth’s crust and atmosphere. The areas are approximate for all elements and exaggerated in the case of the least abundant ones shown here (technetium, promethium, polonium, astatine, radon, francium, radium, actinium and protactinium) so that they are noticeable. Technetium and promethium, shown here in white and marked as synthetic elements, do also occur naturally on Earth, though only in very small amounts. This illustration highlights the speed with which elemental supplies are being used, and draws attention to elements that are at risk of being depleted completely unless recycling routes are developed, as well as those that come from countries in which wars are fought over the ownership of the relevant mineral rights. This table mentions 31 elements (though other sources list other numbers, up to around 70) that are used in smart phones, which are typically replaced more rapidly than necessary.

Advocates of the circular economy such as The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org) cleared the path for the emergence of novel policy frameworks that aim to redesign current economic systems, exemplified by the European Union’s 2013 ‘manifesto for a resource-efficient Europe’. A circular economy is defined as “restorative and regenerative by design, and aims to keep products, components and materials at their highest utility and value at all times”1. Chemistry is crucial for achieving this2,3,4,5,6,7. Chemists understand their role in designing and developing indispensable materials and technologies, but also simultaneously recognize the potentially detrimental effects that this may have on their practice; they are therefore becoming increasingly aware that each step must be designed or reassessed with sustainability in mind.

Green chemistry for linear processes

Since it was first introduced in the 1980s, green chemistry has provided a framework for teaching and performing sustainable chemistry, and has delivered an impetus for developing cleaner products and processes8,9,10 — which have enhanced chemical sustainability in industry and academia. Its twelve guiding principles (Box 1, GC 1–12) focus on the direct sustainability assessment of chemical reactions, and are perfectly suited for the optimization of linear production routes. The developments towards a circular economy, however, require a re-evaluation of what defines a sustainable chemical process, and needs to take into account the people, planet and profit level (referred to as the ‘triple bottom line’)11. Notably, innovative chemistry designed with sustainability in mind is only effective when translated into economically viable applications.

An illustrative example is the reported green synthesis of adipic acid — a key component for the manufacture of nylon-6,6 — by the direct oxidation of cyclohexene with hydrogen peroxide12. Solvent-free conditions are applied (GC 2), avoiding the use of the corrosive nitric acid (GC 3) and thus side-stepping the formation of the environmentally taxing gas nitrous oxide, N2O — a waste product of the current industrial synthesis (GC 4). The green method, however, requires hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, as starting material, which means that this process is currently not commercially viable, since H2O2 is more expensive than the adipic acid product. Although this route obeys green chemistry principles, it violates the value chain. As a result, this green adipic acid synthesis has not been applied industrially, and has therefore not led to an overall increase in sustainability. Thus, accounting for the profit level of the triple bottom line is an essential component in the design of sustainable chemistry.

Other chemical processes may satisfy the green chemistry principles while being economically viable, yet remain unsustainable. For example, the Haber–Bosch process uses iron for the conversion of dinitrogen, N2, into ammonia, NH3, which in turn is used in the production of agricultural fertilizers. It is a key industry showcase for the use of catalysts (GC 9) in increasing energy efficiency (GC 6). The current process requires high temperatures and pressures, and further optimization has stagnated. After its use as fertilizer, large portions of the fixated nitrogen are lost to the environment, causing eutrophication, a global environmental concern, the importance of which should not be underestimated13. The cascade of environmental changes that results includes an increase in water and air pollution, both of which threaten to destabilize the Earth’s system beyond the proposed ‘planetary boundaries’ or “safe operating space” for anthropogenic activities14. This highlights the importance of looking beyond the scientific discovery and analysing the global impact of chemistry using a systems approach15.

Circular chemistry for sustainability

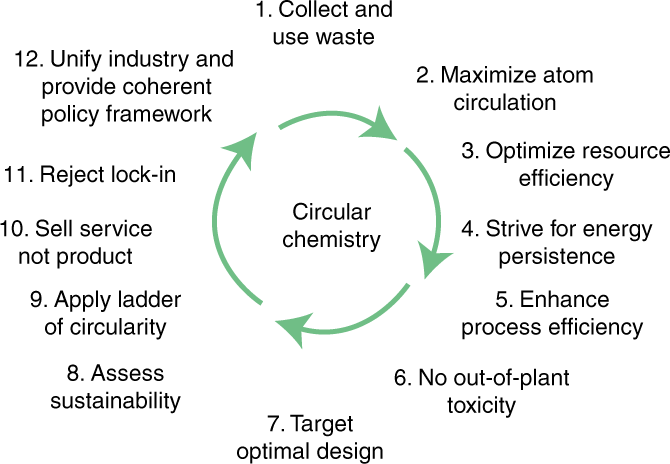

In this Comment, we provide a holistic view on how chemistry can contribute to the development of a circular economy, and formulate twelve principles for a ‘circular chemistry’ (Fig. 2 and Box 2, CC 1–12). In doing so, we provide a framework analogous to that of green chemistry, which has been adapted to facilitate the transition to a circular economy. This approach aims to make chemical processes truly circular by expanding the scope of sustainability from process optimization to the entire lifecycle of chemical products. It promotes, in particular, resource efficiency across chemical value chains and highlights the need to develop novel chemical reactions to reuse and recycle chemicals, to in turn enable development towards a closed-loop, waste-free chemical industry16,17,18,19.

Waste is a resource

Regarding waste as a resource is a prerequisite for circularity. Redirecting waste streams and using them as chemical feedstocks should become ubiquitous in the synthesis of marketable products in order to achieve complete recirculation of molecules and materials (CC 1, Box 2)20,21,22. It is imperative to reduce uncirculated waste in any given process (GC 1, Box 1), yet it will not be possible to eliminate degraded materials or products completely. Waste management will therefore always be required for the effective circulation of materials.

Eutrophication and climate change are two of the biggest global environmental concerns, largely caused by excess use of phosphorus and nitrogen-based fertilizers, and the utilization of fossil fuels, respectively. The excess of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, ammonia and phosphate waste lost to air, water and land perturbs the carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, creating a host of adverse environmental impacts14. To mitigate these environmental concerns and reduce the impact of the resulting waste products on the environment, novel chemical and biochemical conversions are urgently needed that allow for their efficient recovery and recycling.

In order to succeed in eliminating or reusing waste, an optimal process design is needed that allows for the efficient separation, purification, reuse and recycling of waste products in an environmentally benign way. In organic chemistry, Trost’s atom-economy concept stimulated the synthetic efficiency of individual steps (GC 2)23. In a similar manner, at the process level, circular chemistry targets maximizing atom circulation in chemical products along their entire life cycles, regardless of whether chemical bonds are modified or not (Box 2, CC 2). Using waste as resource presents a tremendous challenge for the development of novel chemical conversions that can cope with complex waste mixtures as feedstocks for the production of value-added molecules and materials. Addressing this during the initial design of an entire process will mean that products will lend themselves well to being turned into separated waste-streams at the end of their lifecycle. In turn, this approach should enable the subsequent full recycling of any feedstock and product.

Securing renewability

Circular chemistry seeks to replace today’s linear ‘take–make–dispose’ approach with processes in which materials are continuously cycled back through the value chain for reuse, thereby optimizing resource efficiency and preserving finite feedstocks (CC 3). Renewable resources offer the chemical industry an opportunity to diversify its raw materials base24, but ‘greenwashing’ (presenting a process or product as greener than it actually is) should be prevented: bio-based materials are typically classified as being sustainable, simply because of renewability of the resource (GC 7), yet these resources are often created in a linear production process without sustainable end-of-life options.

Resource renewability alone is not a measure of sustainability. Furthermore, if, for a given application, either oil-based plastics or bio-based plastics can be used (for example PET or bio-PET, produced from mono-ethylene glycol, itself derived from agricultural products), both types of plastics are based on similar building blocks and their function and properties, defined at the molecular level, are also alike. One may ask: ‘what is the difference between an oil-based or bio-based plastic soup in our oceans?’25,26. Unfortunately, cherry-picking a metric (for example, here, renewability over recyclability and environmental risk) is common practice. The popular opinion that oil, gas and coal are harmful, whereas renewables are clean, removes attention from the true sustainability problem: material circulation. What is most important is the use of waste as a resource. Reversible polymerization could be a major driver towards the development of renewable plastics. A few examples of such plastics that display comparable properties to conventional plastics yet can be returned to their monomeric form have been developed that may reshape product life cycles27,28,29,30.

Energy input is an investment

Using waste as a resource can also contribute considerably to the energy efficiency of a chemical product over its entire life cycle31,32. In order to repurpose waste material into a feedstock, it is important to achieve a recirculation of molecules and materials that ensure an energy economy33. For example, CO2 can be converted into a variety of other molecules (ranging from methane to alcohols to amides), which can, in turn, be used for a variety of purposes — but the conversion process shouldn’t necessitate more energy than that offered by the product obtained (CC 4).

This emphasis on the reusability of materials means that their longevity — which requires they remain chemically stable over many product cycles — is valued over their degradability (GC 10)34. By viewing the energy stored in materials as a long-term investment, circular chemistry aims to conserve energy, and thus reduces additional energy inputs. Constant innovation is required to promote the recycling (and therefore the separation) of materials during both a chemical process and the collection of the desired products. These ‘in-process’ developments are followed by ‘post-process’ developments, as the repurposing of the consumed products through chemical or biochemical methods (CC 5) is required to reduce primary feedstock use, optimize resource yields and increase renewability, durability and multi-functionality of chemicals and products.

There is a strong ambition towards developing chemically renewable energies, for example, solar-driven chemistry. Meanwhile, the energy invested in chemical products should be retained as much as possible during circulation. Energy, ultimately derived from natural sources, will always be required for the transportation and processing of materials to enable the full recycling of all chemical elements, especially those that are in limited supply.

Controlled environment

The inherent reactivity of chemicals enables their conversion into value-added compounds, but can also lead to adverse effects. In a similar manner to green chemistry, circular chemistry strives to reduce the harmful impact of these compounds on the environment. Although the use of substances of concern may be unavoidable at some facilities35, these should not be released to the environment (CC 6). This approach requires the continued conglomeration of industrial sites and enhanced cooperation between companies.

Optimal product design should target the most favourable end-of-life state, avoiding persistence in the environment and breakdown into harmful products (CC 7). Biodegradable materials are often seen as sustainable — yet the fact that the product can simply be disposed of in the environment may promote littering. Another issue often overlooked is that micro plastics and polymers partially degraded from a plastic bottle cause more harm to the environment than the original bottle26,36. Here, again, following the green chemistry principles that encourage chemists to design materials for degradation (GC 10) does not unequivocally lead to an increase in sustainability. Therefore, rather than aiming for product degradation, it is preferable to collect waste streams and instead convert them in dedicated plants into value-added materials.

The life cycle assessment and the ladder of circularity

Environmental assessments, typified by the life cycle assessment (LCA), which assesses the impact on the environment of the entire life cycle of a chemical product, should become prevalent to identify inefficiencies in current chemical processes (CC 8)37,38. Such sustainability metrics, which provide information on the environmental impact of a chemical from its design to its disposal39,40 can help to identify opportunities for innovation in a process and can also pinpoint which feedstock is most sustainable to use as resource.

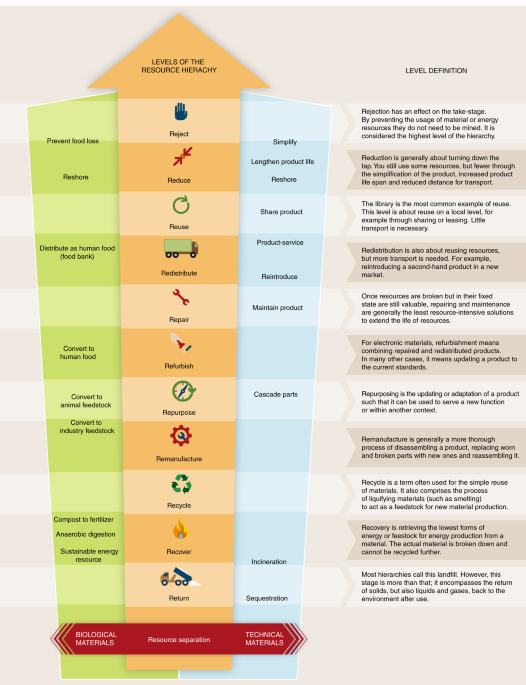

Resource hierarchy (Fig. 3) urges that the necessity of material use is examined by asking the following questions: ‘Do we need this material to achieve our goal?’, ‘Do we need to make something new or can available material be reused or repaired?’, and ‘Does the used product really need to be disposed of?’. The actions associated with these questions are summarized in the ladder of circularity (reject, reduce, reuse, redistribute, repair, refurbish, repurpose, remanufacture, recycle, recover, return, which can be referred to as the ‘11 Rs’)41,42 that provides a means by which to assess the end-of-life options (CC 9). When considering the various routes of circulation, it is required to aim for the highest possible forms of recycling (shown at the top of the ladder). The most desirable courses of action are to avoid or prevent use of resources. Redistribution (reintroducing a used product in a new market) is placed slightly lower than reuse (a widespread example of which is a library) because reusing products in the same location doesn’t require transportation. At the bottom of the ladder, the least desirable options are landfill dumping or incineration of materials as waste. It is true that incineration as a disposal method generates heat, which can be used as energy, but this should be the last resort when there are no viable recycling options.

The widely known ‘3 Rs’ approach — reduce, reuse and recycle — has been expanded and throughout the past few decades a variety of ladders and scales have been used to represent this concept. Figure 3 serves as a visual guide to help the understanding and application of the ‘11 Rs’, depending in particular on the types of materials being used (biological versus technical ones). Whereas biological materials can largely be regenerated, this is not the case for human-made materials, and so for efficient waste management these different types of resources should be kept separate as much as possible.

It is important to account for material separation, purification and degradation to sustain chemical processes. An example of aiming to redesign products for a circular economy while recognizing the triple bottom line is the joint venture between Dutch State Mines (DSM) and Niaga (whose name stems from the backwards spelling of ‘again’). The venture’s first project was the redesign of the carpet-making process, which has been identified as a huge contributor to landfill in the United States and European countries. Separation and recycling of glued carpet was never economically viable; instead, DSM–Niaga now produce their entire carpets out of the same material (polyester) and have also developed a reversible glue that allows carpets consisting of two different materials to be taken apart. This is an example where chemical innovation turned an everyday product in a fully recyclable one, where the waste has value (as another carpet).

Product stewardship

The circular economy relies on a decoupling of material consumption and economic growth43. To promote this, ownership of goods needs to be directed away from the user and back to the producer. This can be achieved by shifting payment models from ownership-based to service-based systems — an example is the use of shared cars. Similarly, in circular chemistry, producers are encouraged to use service-based business models (such as chemical leasing, www.chemicalleasing.org)44to promote efficiency and longevity of the materials over production rate and quantity, and to shift the focus towards a value-added approach targeting the service that is linked with the chemicals.

A successful example of this approach can be found in Egypt. Asea Brown Boveri (ABB) ARAB is a manufacturer of electrical appliances, who resolved high costs in electrostatic powder coating by collaborating with paints and coatings supplier AkzoNobel from 2008. Instead of ABB ARAB buying the coating material per kilogram for their painting operations, the companies devised a process in which expenses were charged per square metre of metal material coated, and powder waste was returned to AkzoNobel for recycling. The arrangement also included the training of workers, resulting in products of better quality and a reduction in the number of reject products, as well as a reduction in maintenance costs. The resulting process is closed-loop, generates nil waste, and ABB ARAB saw a 20% reduction in coating used. A service-based chemical industry is vital to circular chemistry, as companies have the assets and the know-how to retrieve and repurpose chemical products, and the chemical industry is far better equipped to target the management of molecule-circulating loops — for example infrastructure for the reuse or recycling of materials (a step called ‘reverse logistics’) — than the user. This type of industry will lead to the more efficient use of chemicals and to the improved health and safety, environmental and economic benefits (CC 10).

Circumventing lock-ins

Transitioning towards a circular economy requires immediate action. Currently, moving to more sustainable chemical processes is often limited by the status quo of continued process optimization — it is simply easier to keep relying on the established system of production and consumption through, for example, chemical plants and companies. When business-as-usual is preferred over conceptually novel means of providing a service because of the financial cost of adopting the new approach, which often involves the necessary development of supporting technology and infrastructure, the situation can be referred to as a ‘lock-in’45,46,47,48. Therefore, circular chemistry innovations also need to promote transitions and overcome lock-ins to realize market opportunities for long-term sustainability ambitions (CC 11). A chemical innovation befitting circular chemistry yields a process that is both flexible and adaptive. Companies can prevent lock-ins by focusing on entrepreneurs and creating space for change in their available infrastructure from the start.

Finally, in order to facilitate the adoption, development and implementation of circular chemistry, a supportive policy framework is also required (CC 12) to ensure that the value chain is balanced over the whole cycle of materials circulation. Key drivers to induce this transition are: enabling and rewarding chemical and environmental regulations; sustainable supply chains and chemical logistics (https://tfs-initiative.com)49; and optimal university–industry–government relations (which has been referred to as the ‘triple helix’)50.

Conclusions

Within our linear economy, green chemistry has allowed the optimization of chemical processes, leading to less environmentally demanding chemistry practices. In doing so, it has laid the groundwork for an environmentally friendly culture in the chemical discipline. Now, further steps need to be taken towards sustainability. With the development of a circular economy, we introduce a set of principles for sustainable chemistry practice that is analogous to those of green chemistry, and introduce the term circular chemistry.

Circular chemistry offers a holistic systems approach: by making chemical processes truly circular, products can — ideally — be repurposed near-indefinitely, with energy as the only input. The chemical sector has the opportunity to take a leading role in combatting scarcity and environmental crises as a result of ineffective waste management, as the development of novel chemical reactions to reuse molecules and materials will lead to a closed-loop chemical industry. Life cycle thinking and circularity will reinvent chemistry51, and should be the basic principles for developing novel chemical products and processes that use waste as resource. In turn, this will contribute to realizing the circular economy and securing our sustainable future by addressing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals52.