Immune cells that flood the brain may help reduce damage from stroke and multiple sclerosis.

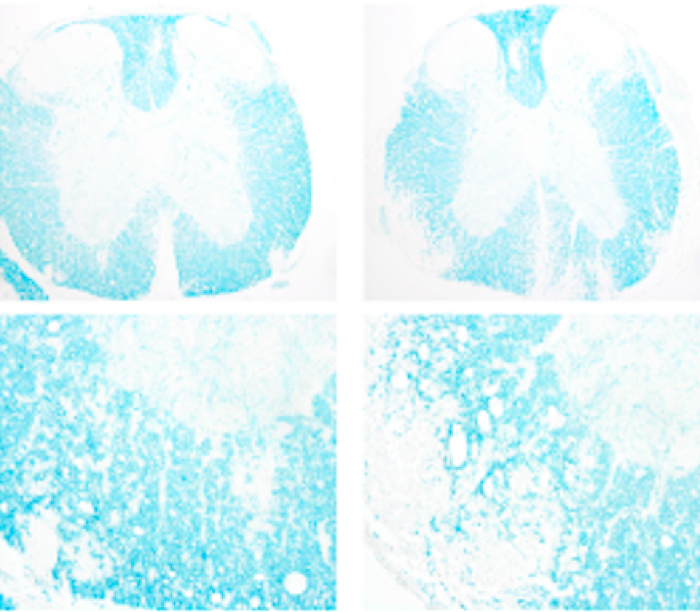

Mice that received plasma (left) had less nerve damage in the spine than those that didn’t (right). Image courtesy of Jennifer Gommerman

The brain has always been mysterious to scientists and clinicians alike, and the mystery only deepens when it comes to the interface of the brain 1and the body’s immune system. The blood–brain barrier has long been identified as the reason that the immune cells don’t quite reach the brain in the same way that they can infiltrate other parts of the body.

Now a pair of recent studies add to the growing body of evidence that immune cells might find their way into the brain to help fight disease like they do elsewhere in the body.

In the first study, published last month in Cell1, scientists show in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis how among immune cells known as B cells, a subset may help reduce the inflammation that is characteristic of the disease. Jen Gommerman, an immunologist at the University of Toronto and one of the authors of the Cell paper, explains that the dogma is that the plasma cells that develop from B cells typically don’t move around from where they’re usually found. “They like to stay in their cozy niches,” Gommerman says. “We challenged that dogma to see whether we could find evidence of plasma cells leaving the gut.”

Gommerman and her colleagues induced a multiple sclerosis–like disease in the animals and transplanted plasma cells into the mice that were also genetically modified to have no plasma cells. Mice that were given plasma cells had less severe disease than those that weren’t. The mice that received the cells had a cumulative clinical score of 40, which indicates these mice had fewer symptoms, such as limb paralysis, than the control group, which received a score of 60.

“The first big surprise was, ‘Oh my gosh, there are all these B cells playing a role,’” says Richard Ransohoff, a neurologist and visiting scientist at Harvard Medical School, when commenting on the Cell paper. Ransohoff says that multiple sclerosis has traditionally been thought of as a disease in which B cells are somehow harmful, but this study challenges that. “Everyone’s trying to figure out what are the bad things B cells are doing, and here this paper is saying that B cells are doing some good things.”

Since the gut is where plasma cells are usually found, Gommerman and her colleagues also manipulated the gut microbiomes of the mice by giving them a type of microbe known as a protist to increase the number of plasma cells that they observed to be beneficial against multiple sclerosis symptoms. The mice given the protists were less likely to develop disease; 7 out of 11 mice in the group given the protists showed symptoms of the disease compared with 9 out of 11 mice in the non-manipulated group. For the seven of these mice that showed signs of disease, it was less severe, as measured by a lower clinical score, than that in mice that didn’t receive protists. “I don’t think we’re going to be giving people protists,” Gommerman says, since these microbes are often pathogenic in humans, “but we could start to explore manipulating the microbiome as a co-therapy along with traditional multiple sclerosis treatment.”

Safety in numbers

Another study, published last month in Nature2, suggests that a type of T cell that typically resides in the organs of the lymphatic system, including the spleen, might make its way to the brain to aid in recovery from stroke. These scientists found an unusually large number of a subset of T cells known as regulatory T cells in the brains of mice following a stroke.

“Usually you’d find maybe 100 of these cells in the brain, but after injury we found 10,000 or so,” says Akihiko Yoshimura, an immunologist at Keio University in Tokyo and senior author of the study. “It’s a huge accumulation.”

Even beyond the number of regulatory T cells in the brain, the researchers were surprised to see that these cells responded to the neurotransmitter serotonin in a way that had previously not been known. “This is very different from other T regulatory cells,” Yashimura explains.

The cells grew in number in response to serotonin, and this expansion is what seemed to have a beneficial effect when it came to recovery from stroke. The researchers also found that the infiltration of T cells into the brain seemed to be driven by two signaling proteins and that mice that were injected with these proteins following stroke recovered faster than mice in the control group. For instance, in one test of how quickly mice regained their ability to make right turns (a movement that was lost as a result of stroke), mice that were injected with either of the two signaling proteins were almost back to normal within 15 days, whereas the control mice had made little progress towards regaining their ability to turn corners.

Ransohoff says that what is remarkable about the Nature study is its focus on the chronic stage of stroke. “What is particularly noteworthy is that in the world of stroke therapy, everything is focused on the first six hours post-stroke, and this group is focused on regenerative medicine.” Yoshimura and his colleagues looked at mice two weeks following a stroke.

Some scientists are cautious about therapeutic takeaways for human beings. When it comes to stroke, “We don’t know yet which cell types are involved and what role they play,” says Alexander Flügel, a neuroimmunologist at the University of Göttingen in Germany. “We are at the very beginning of understanding this, and I would be skeptical about therapeutic takeaways.”

Still, there has been some evidence to suggest that the immune cells that infiltrate the brain could be used to our advantage when treating disease. In one study3, ten patients with a recurrent form of the brain cancer glioblastoma were treated with T cells that were extracted from their bodies and modified to target a specific protein in the brain. The researchers found that the therapy was well tolerated and seemed to elicit an immune response in the brain against the tumor, although, given the late stage and severity of the disease, the scientists weren’t able to determine much clinical benefit.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)