美연구진, 집돼지 뇌 32개 분리해 실험…죽은 지 4시간 만에 일부 기능 되살려

인식·지각 등 고차원적 기능은 못 살려

‘몸과 분리된 뇌’ 등 윤리적인 논란도

식량 생산을 목적으로 사육되는 돼지의 경우 동물실험이 금지돼 있으나 최근 돼지의 뇌 복원 연구가 성공함에 따라 가축용 돼지를 이용한 다양한 동물실험이 시도될 것으로 예상된다. 가축까지 실험 대상에 오르며 실험동물에 대한 윤리 논쟁이 더욱 거세질 것으로 보인다.네이처 제공“

창조주여, 제가 부탁했습니까? 진흙에서 저를 빚어 사람으로 만들어 달라고? 제가 애원했습니까? 어둠에서 절 끌어내 달라고?”

200여년 전인 1818년 영국 작가 메리 셸리(1797~1851)가 쓴 괴기소설 ‘프랑켄슈타인-근대의 프로메테우스’ 서문에 실린 ‘실낙원’의 한 구절이다. 무생물에 생명을 부여할 수 있는 방법을 알아낸 스위스 과학자 빅터 프랑켄슈타인 박사는 시체를 이용해 8피트(약 244㎝)의 인조인간을 만들어 생명을 불어넣는다. 이렇게 만들어진 괴물은 인간 이상의 힘을 발휘하고 자신과 똑같은 형태의 신부까지 요구했다. 그렇지만 새로운 인종이 나와 인간을 멸망시킬까 두려웠던 프랑켄슈타인 박사는 괴물의 요구를 거부했다가 살해당한다.

셸리는 소설을 쓰면서 영국 화학자 험프리 데이비의 전기분해 기술, 찰스 다윈의 할아버지 에라스무스 다윈이 수행한 자연발생 실험 같은 당대 최고 수준의 과학기술을 활용했지만 사람과 똑같은 형태와 기능을 갖춘 인조인간을 만든다는 생각은 공상에 불과했다. 그런데 최근 생물학과 생체공학 기술이 발달하면서 ‘프랑켄슈타인’ 몬스터 기술이 현실화되는 것 아니냐는 지적이 나오고 있다.

이 같은 상황에서 미국 예일대 의대, 코네티컷 재향군인의료시스템 재활연구센터, 보스턴대 의대, 피츠버그대 신경학과, 이탈리아 파비아대 생물학·생명공학과 공동연구팀은 죽은 지 몇 시간이 지난 돼지의 뇌를 다시 살려내는 실험 일부를 성공하고 세계적인 과학저널 ‘네이처’ 18일자에 발표했다. 이번 연구 결과는 완벽하지는 않지만 죽은 생명체의 뇌 기능 일부를 다시 회복시켰다는 점에서 전 세계 과학계와 윤리학계에 충격을 안겨 주고 있다.

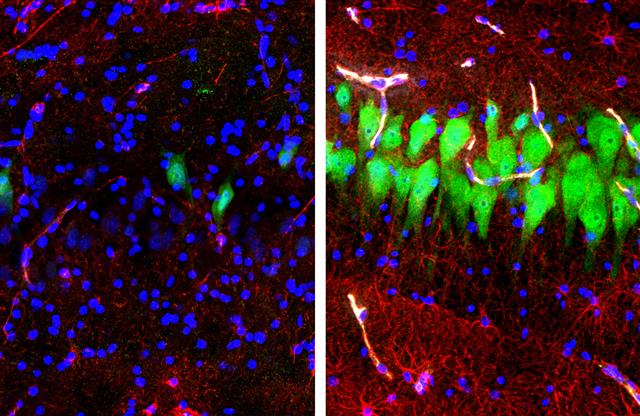

식량 생산을 목적으로 사육되는 돼지의 경우 동물실험이 금지돼 있으나 최근 돼지의 뇌 복원 연구가 성공함에 따라 가축용 돼지를 이용한 다양한 동물실험이 시도될 것으로 예상된다. 가축까지 실험 대상에 오르며 실험동물에 대한 윤리 논쟁이 더욱 거세질 것으로 보인다. 뇌의 해마CA3 부위를 형광 처리해 죽은 뒤 방치된 경우(왼쪽)와 브레인엑스 기술로 처치(오른쪽)된 것을 비교한 사진. 브레인엑스 기술로 처리되지 않을 경우 사후 10시간이 지나면 세포핵(밝은 부분)을 제외하고는 뉴런과 성상교세포는 빠르게 분해돼 거의 사라지게 된다. 네이처·美예일대 의대 제공

연구팀은 보통 동물실험을 할 때 사용하는 실험용 무균돼지가 아닌 식재료 가공시설에서 얻은 생후 6~8개월 된 집돼지의 뇌 32개를 가지고 실험했다. 실험에 사용된 돼지의 뇌는 죽은 뒤 4시간이 지난 것들이었다. 보통 포유류의 뇌는 산소 공급에 매우 민감하기 때문에 짧은 시간 동안만 혈류가 중단되더라도 산소와 에너지 공급이 끊겨 회복 불가능한 뇌 손상을 일으키는 것으로 알려져 있다.

연구팀은 분리된 돼지의 뇌를 자체 개발한 ‘브레인 엑스’라는 장치에 넣은 다음 보호제와 안정제 등을 섞은 특수 용액을 혈액 대신 뇌 혈관에 주입해 영양과 산소를 공급하며 뇌 변화를 관찰했다.

그 결과 뇌세포 구조, 뇌혈관 구조가 정상적으로 회복되고 신경과 세포를 파괴하는 염증 반응이 줄어드는 한편 시냅스에서 자발적인 움직임을 보이는 것이 관찰됐다. 그렇지만 인식과 지각 같은 고차원적 뇌 기능을 위해 필요한 전기적 활동은 관찰되지 않았다고 연구팀은 설명했다.

이번 연구는 2013년 미국 버락 오바마 정부가 3조 5000억원을 투자해 진행 중인 뇌연구 프로젝트인 ‘브레인 이니셔티브’의 지원을 받아 진행됐다.

연구를 주도한 네나드 세스탄 예일대 의대(신경과학) 교수는 “이번 연구는 아직 초보적인 수준이지만 혈관의 촘촘한 연결 네트워크를 통해 뇌에 보호제를 공급하면 심각한 외상후 생존율을 높이고 신경학적 결손을 줄여 뇌사의 가능성을 획기적으로 줄일 수 있음을 보여 준 것”이라고 설명했다.

이번 연구 결과에 대해 생명윤리학자인 현인수 미국 케이스웨스턴리저브대 의대 교수는 “죽은 돼지의 뇌를 사실상 살려낸 이번 연구는 포유류의 뇌에 혈액 공급이 중단되면 몇 분 안에 사망한다는 기존의 생각을 뒤집는 것”이라며 “몸과 분리됐지만 살아 있는 뇌를 인격체로 보아야 하는지, 이런 연구에 대한 가이드라인을 어떻게 설정해야 하는지 등 논란거리들을 남겼다”고 설명했다.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

[美예일대 연구진 주도…”뇌 질환 치료에 획기적인 변화”]

죽은 돼지 뇌 해마 부위를 형광물질로 관찰한 사진. (사진 왼쪽부터)죽은 지 10시간이 지난 돼지의 뇌, ‘브레인엑스’로 일부 뇌세포 기능을 회복시킨 뇌/사진=네이처

미국 연구진이 죽은 지 4시간이 지난 돼지의 뇌 일부 기능을 되살리는 데 성공했다. 학계는 지금까지 죽은 뇌세포는 되살릴 수 없다고 믿어왔다. 이 같은 통설을 뒤집은 이번 연구는 뇌 손상·질환 관련 치료법 개발에 획기적인 변화를 가져올 전망이다.

이번 연구를 주도한 미국 예일대 의대의 네나드 세스탄 교수 연구진은 죽은 돼지의 뇌에 인공 혈액을 넣는 방식으로 돼지 내 일부 세포 기능을 일정 시간 재가동시키는데 성공했다고 18일 밝혔다.

포유류의 뇌는 혈액을 통한 산소·영양분 공급이 4분 이상 끊어지면 심각한 뇌 손상을 입는다. 연구진에 따르면 사후 4시간이 지난 32마리의 돼지의 사체에서 뇌를 분리한 뒤, ‘브레인EX’라는 시스템으로 동맥에 보존제·안정제, 산소 등이 포함된 혈액 같은 특수용액을 집어넣었다.

그 결과, 돼지의 뇌 일부 신경·혈관세포 기능이 정상화되는 등 정상 구조를 되찾았다. 또 뇌 세포를 파괴하는 염증 반응이 줄어드는 한편 신경세포끼리 신호를 주고 받는 시냅스 반응도 감지됐다. 이런 과정은 6시간 동안 지속됐다.

하지만 인식 및 지각 같은 고차원적인 뇌 기능은 재활성화 되지 못했다는게 연구팀의 설명이다.

네나드 세스탄 교수는 “이번 연구로 향후 뇌졸중 등 뇌 손상·질환에 의해 정지된 뇌 기능을 회복시키는 치료법 개발에 기여할 수 있을 것”이라고 말했다. 이번 연구성과는 국제학술지 ‘네이처’에 게재됐다.

한편, 일각에선 이번 연구에 대한 윤리적 문제를 제기한다. 현인수 미국 케이스웨스턴리저브대 교수는 이날 논평에서 “인간의 뇌도 복원할 수 있다는 기대감에 뇌사자의 장기 기증이 줄어들 수 있다”고 우려했다.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

Pig experiment challenges assumptions around brain damage in people

The restoration of some structures and cellular functions in pig brains hours after death could intensify debates about when human organs should be removed for transplantation, warn Stuart Youngner and Insoo Hyun.

In this week’s Nature, researchers describe restoring certain structural and functional properties to pigs’ brains, even four hours after the animals had been killed1. They used an artificial perfusion system called BrainEx.

Electrophysiological monitoring did not detect any kind of neural activity thought to signal consciousness, such as any evidence of signalling between brain regions (see ‘Between life and death’). Nonetheless, the study challenges the long-held assumption that large mammalian brains are irreversibly damaged a few minutes after blood stops circulating. It also raises the possibility that researchers could get better at salvaging a person’s brain even after the heart and lungs have stopped working.

Advances following on from the BrainEx study could exacerbate tensions between efforts to save the lives of individuals and attempts to obtain organs to donate to others. (Such advances could also affect the use of human brains and brain tissue in research.)

In our view, as the science of brain resuscitation progresses, some efforts to save or restore people’s brains might seem increasingly reasonable — and some decisions to forego such attempts in favour of procuring organs for transplantation might seem less so.

The transplant community, neuroscientists, emergency medical personnel and other stakeholders must debate the issues2. Eventually, it might be useful for groups such as the US National Academy of Medicine to offer guidelines for physicians and hospitals. These would help to protect the interests of individuals for whom sufficient recovery is a possibility, as well as the interests of potential organ recipients.

Determination of death

For decades, bioethicists and transplantation-policy researchers have had to wrestle with the question of when to switch from trying to save someone’s life to trying to save their organs for the benefit of another person.

Invariably, this comes down to a moral decision — namely about futility, which is a contentious and value-laden concept3. There are few data to support decisions. And clinicians disagree about when there is a chance of recovery. There is also little consensus on what level of recovery is ‘good enough’ from the perspective of patients and their families, as well as when these factors are weighed against limited medical resources.

In most countries, a person can be legally declared dead if they show irreversible loss of all brain function (brain death) or irreversible loss of all circulatory function (circulatory death).

In recent decades, most organs for transplant have been taken from those who have been declared brain dead, often after a catastrophic brain injury resulting from a stroke, trauma or prolonged lack of oxygen to the brain, caused for instance by drowning. (In these cases, the person’s heart and lung functions are maintained in the intensive care unit.)

Increasingly, however, those who are declared dead after their hearts and lungs have stopped working are being deemed eligible for organ donation. This shift has largely been driven by an increased need for organs as transplantation surgeries have become more successful. According to the US non-profit organization the United Network for Organ Sharing, someone is added to the US transplant waiting list every ten minutes. In 2017, around 18 people in the United States died every day while waiting for a transplant.

If technologies similar to BrainEx are improved and developed for use in humans, people who are declared brain dead (especially those with brain injuries resulting from a lack of oxygen) could become candidates for brain resuscitation rather than organ donation. Certainly, it could become harder for physicians or family members to be convinced that further medical intervention is futile.

For people who have been declared dead on the basis of circulatory criteria, matters could become even more complex.

Today, there are two main protocols for obtaining organs in these cases. One occurs in individuals who have severe brain injuries but are not brain dead. It is called controlled donation after circulatory determination of death (controlled DCDD)4.

Here, after carers obtain consent, they switch off the person’s mechanical ventilator and any other life support that might be in use in the operating room. The patient is then declared dead 2–5 minutes after their heart stops beating. Because adequate testing for brain death is impossible in the race to obtain healthy organs, it is assumed that the individual has had an irreversible loss of brain function.

The second protocol (uncontrolled DCDD) is practised mainly in Europe5. It generally occurs after a person has had a heart attack in a non-medical setting4. In these cases, after paramedics have declared resuscitative efforts futile, nothing is done for around 5–20 minutes5. Next, steps are taken to try to preserve the organs. These might include resuming cardiopulmonary resuscitation to restore circulation; introducing cooling fluids through an artery in the groin; or even a technique that oxygenates the blood and pumps it throughout the body (known as extra corporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO).

Even now, clinicians and bioethicists disagree over how long is long enough for paramedics to keep trying to resuscitate. Practitioners use various rules of thumb, such as ‘declare death after 30 minutes of unsuccessful resuscitative efforts’, and can refer to published guidelines6. But as the US neurologist James Bernat has pointed out, such rules “are difficult to apply in practice because each CPR is a unique event with different variables”7. Data are scant, but one study of people who died of heart attacks in hospitals in the United States found that patients were declared dead with more certainty after longer resuscitative efforts8.

In some countries, ambulances carry special equipment to restore circulation to the organs of people who have been declared dead after a heart attack.Credit: Leon Neal/Getty

Questions about the term ‘irreversible’ haunt both protocols. Does this mean that the care team is unable to reverse a situation, or that they have reasonably decided not to attempt to? Unsurprisingly, most advocates for transplantation favour the latter view. Some have even argued that further efforts to restore people’s brains at the expense of organ procurement would divert much-needed medical resources and potentially increase the number of people with severe disabilities9.

Heightening the tension are concerns among bioethicists and medical practitioners that brain function could be recovered in some bodies that have been put on ECMO. Some organ-recovery teams in the United States10 and Taiwan11 have tried to prevent this by inserting a thoracic aortic occlusion balloon to stop the pumped blood from reaching the brain. This intervention was deemed a “serious problem” by a US Department of Health and Human Services panel because it raises “causation questions about physicians’ active complicity in the patient’s death”4.

Lastly, there is considerable variation between countries about what is morally and legally acceptable. In France and Spain, ECMO equipment can be transported in a special ambulance to wherever the patient is. In the United States, the technique is controversial and rarely used.

These debates and decisions could become much more fraught if advances in research challenge assumptions about the brain’s inability to recover from an absence of oxygen, or even just hint at the possibility that consciousness can be restored after a person’s heart has stopped beating. Ultimately, more people could become candidates for brain resuscitation rather than for organ donation.

Healthy debate

Balancing the competing interests of developments in resuscitation and transplantation comes down to values, as well as science. Different people have different ideas about how to best save and improve lives.

In our view, the BrainEx study, and the follow-up work it will surely inspire, flag the need for more open discussion. Debate involving everyone — from neuroscientists and policymakers to patients and medical personnel — could help to clarify which criteria make someone eligible for organ donation versus resuscitation. Such discussions can also explore how to ensure that organ donation can be integrated into end-of-life care with minimal controversy.

Two institutions are well placed to take the lead and bring the relevant stakeholders together: the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and the UK Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Both have held public meetings and produced multidisciplinary reports on controversial areas of science, medicine and ethics for decades. In 2006, for example, workshops held over a year involving researchers, health-care professionals and comments from the public led to an NAS report evaluating various proposals to increase organ donations, and their potential impact on people from minority ethnic groups and those who are socio-economically disadvantaged12.

Researchers are a long way from being able to restore structures and functions in the brains of people who would today be declared dead. But, in our view, it is not too early to consider how this type of research could affect the growing population of critically ill patients who are waiting for kidneys, livers, lungs or hearts.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

Pig brains kept alive outside body for hours after death

Revival of disembodied organs raises slew of ethical and legal questions about the nature of death and consciousness.

The pigs whose brains were used in the study had been killed at a slaughterhouse for meat.Credit: Chaiwat Subprasom/Reuters

In a challenge to the idea that brain death is final, researchers have revived the disembodied brains of pigs four hours after the animals were slaughtered. Although the experiments stopped short of restoring consciousness, they raise questions about the ethics of the approach — and, more fundamentally, about the nature of death itself. The current legal and medical definitions of death guide protocols for resuscitating people and for transplanting organs.

Details of the pig-brain experiments appear in a paper1 published on 17 April in Nature. Researchers at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, hooked the organs to a system that pumped in a blood substitute. The technique restored some crucial functions, such as the ability of cells to produce energy and remove waste, and helped to maintain the brains’ internal structures.

“For most of human history, death was very simple,” says Christof Koch, president and chief scientist of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, Washington. ”Now, we have to question what is irreversible.”

In most countries, a person is considered to be legally dead when brain activity ceases or when the heart and lungs stop working. The brain requires an immense amount of blood, oxygen and energy, and going even a few minutes without these vital support systems is thought to cause irreversible damage.

Since the early twentieth century, scientists have conducted experiments that keep animals’ brains alive from the moment the heart stops, by cooling the brains and pumping in blood or a substitute. But how well the organs functioned afterwards is unclear2. Other studies have shown that cells taken from brains long after death can perform normal activities, such as making proteins3. This made Yale neuroscientist Nenad Sestan wonder: could a whole brain be revived hours after death?

Sestan decided to find out — using severed heads from 32 pigs that had been killed for meat at a slaughterhouse near his lab. His team removed each brain from its skull and placed it into a special chamber before fitting the organ with a catheter. Four hours after death, the researchers began pumping a warm preservative solution into the brain’s veins and arteries.

The system, which the researchers call BrainEx, mimics blood flow by delivering nutrients and oxygen to brain cells. The preservative solution the team used also contained chemicals that stop neurons from firing, to protect them from damage and to prevent electrical brain activity from restarting. Despite this, the scientists monitored the brains’ electrical activity throughout the experiment and were prepared to administer anaesthetics if they saw signs that the organ might be regaining consciousness.

Time trial

The researchers tested how well the brains fared during a six-hour period. They found that neurons and other brain cells had restarted normal metabolic functions, such as consuming sugar and producing carbon dioxide, and that the brains’ immune systems seemed to be working. The structures of individual cells and sections of the brain were preserved — whereas cells in control brains, which did not receive the nutrient- and oxygen-rich solution, collapsed. And when the scientists applied electricity to tissue samples from the treated brains, they found that individual neurons could still carry a signal.

But the team never saw coordinated electrical patterns across the entire brain, which would indicate sophisticated brain activity or even consciousness. The researchers say that restarting brain activity might require an electrical shock, or preserving the brain in solution for extended periods to allow cells to recover from any damage they sustained while deprived of oxygen.

Sestan, whose team has used its technique to keep pig brains alive for up to 36 hours, has no immediate plans to try to restore electrical activity in a disembodied organ. Instead, his priority is to find out how long his team can maintain a brain’s metabolic and physiological functions outside the body. “It is conceivable we are just preventing the inevitable, and the brain won’t be able to recover,” Sestan says. “We just flew a few hundred metres, but can we really fly?”

The BrainEx system is far from ready for use in people, he adds, not least because it is difficult to use without first removing the brain from the skull.

Questions multiply

Nevertheless, the development of technology with the potential to support sentient, disembodied organs has broad ethical implications for the welfare of animals and people. “There isn’t really an oversight mechanism in place for worrying about the possible ethical consequences of creating consciousness in something that isn’t a living animal,” says Stephen Latham, a bioethicist at Yale who worked with Sestan’s team. He says that doing so might be ethically justifiable in some cases — for instance, if it enable scientists to test drugs for degenerative brain diseases on the organs, rather than people.

Gauging awareness in a brain outside a body would probably be difficult, given that the organ’s surroundings would differ so radically from its natural environment. “We could imagine that brain could be capable of consciousness,” says George Mashour, a neuroscientist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor who studies near-death experiences. “But it’s very interesting to think about what kind of consciousness, in the absence of organs and peripheral stimulation.”

The latest study also raises questions about whether brain damage and death are permanent. Lance Becker, an emergency-medicine specialist at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, says that many physicians assume that even minutes without oxygen can cause irreversible harm. But the pig experiments suggest that the brain might stay viable for much longer than previously thought, even without outside support. “This paper throws a hand grenade into the middle of what the common beliefs are,” says Becker. “We may have vastly underestimated the ability of the brain to recover.”

That could have practical and ethical consequences for organ donation. In some European countries, emergency responders who cannot resuscitate a person after a heart attack will sometimes use a system that preserves organs for transplantation by pumping oxygenated blood through the body — but not the brain. If a technology such as BrainExbecomes widely available, the ability to extend the window for resuscitation could shrink the pool of eligible organ donors, says Stuart Youngner, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

“There’s a potential conflict here between the interests of potential donors — who might not even be donors — and people who are waiting for organs,” he adds.

Far to go

In the meantime, scientists and governments are left to confront the legal and ethical quandaries related to the possibility of creating a conscious brain without a body. “This really is a no-man’s land,” says Koch. “The law will probably have to evolve to keep up.”

Koch wants a broader ethical discussion to take place before any researcher tries to induce awareness in a disembodied brain. “It is a big, big step,” he says. “And once we do it, it’s impossible to reverse it.”

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

Part-revived pig brains raise slew of ethical quandaries

Researchers need guidance on animal use and the many issues opened up by a new study on whole-brain restoration, argue Nita A. Farahany, Henry T. Greely and Charles M. Giattino.

Scientists have restored and preserved some cellular activities and structures in the brains of pigs that had been decapitated for food production four hours before. The researchers saw circulation in major arteries and small blood vessels, metabolism and responsiveness to drugs at the cellular level and even spontaneous synaptic activity in neurons, among other things. The team formulated a unique solution and circulated it through the isolated brains using a network of pumps and filters called BrainEx. The solution was cell-free, did not coagulate and contained a haemoglobin-based oxygen carrier and a wide range of pharmacological agents.

The remarkable study, published in this week’s Nature1, offers the promise of an animal or even human whole-brain model in which many cellular functions are intact. At present, cells from animal and human brains can be sustained in culture for weeks, but only so much can be gleaned from isolated cells. Tissue slices can provide snapshots of local structural organization, yet they are woefully inadequate for questions about function and global connectivity, because much of the 3D structure is lost during tissue preparation2.

The work also raises a host of ethical issues. There was no evidence of any global electrical activity — the kind of higher-order brain functioning associated with consciousness. Nor was there any sign of the capacity to perceive the environment and experience sensations. Even so, because of the possibilities it opens up, the BrainEx study highlights potential limitations in the current regulations for animals used in research.

Most fundamentally, in our view, it throws into question long-standing assumptions about what makes an animal — or a human — alive.

Signs of what?

The pig brains used in the study, which was conducted by a team based largely at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, produced a flat line on an electroencephalogram (EEG) of brain activity. Had any degree of sentience been recovered, let alone consciousness, one would expect to see low-amplitude waves in the alpha (8–12 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) range, at the very least3,4. In consultations with the Neuroethics Working Group of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) BRAIN Initiative and in discussions with us, the researchers have stated that if they had detected such activity, they would have administered anaesthetic agents to prevent any experience similar to pain or distress, and would have reduced the brain temperature to swiftly quell the activity.

Researchers already study whole organs, and maintain cellular activity for a few seconds to minutes in slices of animal and human brains. Thus, on the face of it, in the absence of EEG activity, the BrainEx study does not raise fundamentally different issues from those encountered in the use of animal or human brain tissue after death.

Yet, until now, neuroscientists and others have assumed two things. First, that neural activity and consciousness are irretrievably lost within seconds to minutes of interrupting blood flow in mammalian brains. Second, that, unless circulation is quickly restored, there is a largely irreversible progression towards cell death and the death of the organism1.

The BrainEx study used pig brains that had received no oxygen, glucose or other nutrients for four hours. As such, it opens up possibilities that were previously unthinkable.

Take the lack of EEG activity. This activity could have been lost irreversibly when the pigs were slaughtered. Another possibility, however, is that the lack of EEG activity was a function of the study design. The researchers used several chemical agents in their solution that inhibit neural activity, hypothesizing that the tissues would be more likely to show some recovery if cellular activity were reduced. Had these blockers been removed at some point, perhaps the team would have detected EEG activity.

Another possibility needing investigation is that something similar to shock treatment for the heart is required to reset the firing of neurons in the brain to a level that is detectable. Or maybe it takes longer than six hours (the length of the BrainEx perfusion, following the four hours after death) for the cells to recover sufficiently for this kind of brain activity to emerge5. Physicians sometimes lower the core body temperatures of people who have had a heart attack, to induce a hypothermic coma. This can limit damage caused by swelling in the brain, for instance, and aid cellular recovery. In these cases, patients seem to need at least 24 hours of ‘cooling treatment’.

Obviously, more data are needed, including the replication of the BrainEx findings in other laboratories by other groups. But we’re reminded of a line from the 1987 film The Princess Bride: “There’s a big difference between mostly dead and all dead. Mostly dead is slightly alive.” Even with all the unknowns, the discovery that mammalian brains can be made to seem ‘slightly alive’, hours after the animals had been killed, has implications that ethicists, regulators and society more broadly must now think through.

Animal research

To be clear, the BrainEx study did not breach any ethical guidelines for research. The team sought guidance from Yale University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which exists to ensure that the use of animals aligns with what is required by US law for federally funded research. The committee decided that oversight was unnecessary. The pigs, having been raised as livestock, were exempt from animal welfare laws and were killed before the study started. In the United States, the 1966 Animal Welfare Act is the only federal law that regulates how animals are treated in research, and applies to either living or dead animals. It explicitly excludes animals raised for food. Meanwhile, the policies and regulations of the US Public Health Service, which funds most US research involving animals — mainly through the NIH — do not specify any protections for animals after their death.

Had the research been conducted outside the United States, the response from ethics or regulatory bodies would almost certainly have been the same. The European Union’s Directive on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes largely aims to prevent (or minimize) any pain, suffering or distress experienced by live animals. It, too, specifically excludes animals raised for agriculture (see go.nature.com/2cpdgjr). In China, both the Ministry of Science and Technology and the provincial bureaus of science and technology ensure that researchers follow local regulations and that they abide by the National Standard on Laboratory Animal Welfare in China6. Here, too, the protections exclude animals raised for food, and the main focus is on eliminating or reducing live animals’ potential pain and distress.

In our view, new guidelines are needed for studies involving the preservation or restoration of whole brains, because animals used for such research could end up in a grey area — not alive, but not completely dead. Five issues in particular need addressing.

A woman is silhouetted as she walks past an exhibition piece displaying a brain slice from a person who underwent surgery for epilepsy in the 1950s.Credit: Brian Snyder/Reuters

First, how should researchers try to detect signs of consciousness or sentience? On its own, EEG activity would not reliably signal a conscious brain; such activity is nearly always detected in people who are under general anaesthesia7. EEG activity might provide an appropriate measure should it be detected along with responsiveness to transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) — a non-invasive way of stimulating brain activity, using a magnetic coil held near the head. Together with other measures, this would determine the brain’s perturbational complexity index, a way of identifying the level of consciousness8. Furthermore, recent research in humans using functional magnetic resonance imaging indicates that certain patterns of neuronal activity may provide a correlate for consciousness9.

Second, which species make appropriate models for this type of research on brain perfusion? And what kinds of research and results would be needed to justify the use of other models? (In our view, investigators should proceed cautiously with testing in other mammals, particularly in pigs, dogs or primates, at this time10.)

Third, until more is known, is the use of neuronal activity blockers sufficient to safeguard against the emergence of capabilities associated with sentience, such as the capacity to feel pain? It might be necessary to apply BrainEx or similar systems to mice or rats, both with and without neuronal activity blockers, to better understand the blockers’ role.

Fourth, under which scenarios should anaesthetics be used in follow-on studies, to safeguard against the possibility of inducing any experience similar to pain or distress? And under what scenarios might it be permissible not to use them? (We think that the use of anaesthetics in follow-on studies should be mandatory at this time, given all of the unknowns.)

Finally, for how long should BrainEx or similar artificial circulatory systems be run? Such systems might be effective for only a certain period of time, or there could be a limit as to how much recovery can be achieved. This knowledge will inform analyses of risks and benefits.

Human research

Although it is a long way off, researchers might one day consider using a system similar to BrainEx to treat humans for brain damage caused by a lack of oxygen. Until now, neuroscientists and physicians have assumed that the cell death caused by this is irreversible. Treatment generally involves working with a person’s remaining healthy brain tissue to help rehabilitate mobility, motor and other skills.

Before developing whole human-brain models outside the body — and certainly before the use of brain perfusion in the clinic — investigators need to arm people with enough information for them to make informed decisions. Most fundamentally, patients or donors will need to understand what kinds of brain activity could result and what that activity could mean. They will also need to know the chances of recovery being only partial, and the implications that will have.

Another question is what information, if any, could plausibly be retrieved from the brain. Various groups are developing ways to decode the neural activity of living people, for instance to probe their memories or the images they have seen in their dreams11,12. Could such approaches one day be applied to brains after death?

Such possibilities (if they come to pass at all) are far in the future. Yet we need to think through at least some of them now. Hundreds of people worldwide have already paid to have their brains frozen and stored, in the hope that scientists will one day be able to revive them. It’s easy to imagine misapplications of brain perfusion following the publication of the BrainEx study alone.

Guidelines

It might not be easy for others to replicate the study, despite the BrainEx team providing detailed information on the device, perfusate and methods. As a first step, the investigators, their home institutions and the NIH should facilitate the transfer of the technology and know-how to other researchers and institutions. Any follow-up and independent studies should be just as transparent as this one.

Crucially, future researchers will need guidance through the potential scientific, ethical and political questions opened up by this research.

Precedents exist. Internationally, research involving stem cells derived from human embryos has successfully been steered by the 2005 Guidelines for Human Embryonic Stem Cell Research released by the US Institute of Medicine and US National Research Council — the substance of which was almost entirely adopted by the International Society for Stem Cell Research. Ongoing efforts to set guidelines for human genome-editing research hold lessons, too. Key actors here are the US National Academy of Sciences, the US National Academy of Medicine, the UK Royal Society, the Hong Kong Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics.

In other contexts, such as in biomedical engineering (see, for example, go.nature.com/2t6kon5), artificial intelligence13 and debates around the definition of death14, international conferences are being held to help find common ground across countries and to develop frameworks that enable responsible scientific progress.

We think that the latest research on brain resuscitation demands the same kind of international attention. A starting point could be the guiding principles issued last December by the Neuroethics Working Group of the NIH BRAIN Initiative, which held a 2018 workshop on research with human neural tissue15.

Citizens must be part of the process. Engaging non-scientists in delineating the ethical boundaries of this research doesn’t guarantee its public acceptance in the future; and nor should it, necessarily. But not engaging other stakeholders could help to precipitate its rejection.

In our view, discussion about the appropriate path for this research should not wait for follow-up studies. The Yale group was conscientious and consulted the local institutional IACUC, Yale bioethicists, NIH programme officers and even the NIH Neuroethics Working Group. The researchers did what they could, and probably more than many would have done, to ensure that they were acting appropriately in a void of ethical analysis on the issue.

Now is the time to fill that void.

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

아래는 2021년 10월 21일 뉴스입니다~

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

돼지 신장을 사람에게…이종간 이식 실험 첫 성공

장기이식 실험 연구에 사용된 유전자 편집 돼지 ‘갈세이프’. 리리비코어 제공

돼지는 사람과 장기 크기가 가장 비슷한 동물이다. 따라서 오래 전부터 사람한테 장기를 이식해 줄 수 있는 후보로 꼽혀 왔다. 그러나 이종간 장기 이식은 면역 거부 반응을 일으킨다는 문제가 있다.

최근 미국 연구진이 면역 거부 반응 없이 돼지의 신장을 사람에게 이식하는 실험에 처음으로 성공했다. 유전자 편집을 통해 거부반응 유발 물질을 없앤 것이 효과를 발휘했다.

미국 뉴욕대 랑곤헬스(NYU Langone Health) 메디컬센터의 로버트 몽고메리 이식연구소 소장 연구진은 지난 9월 신부전으로 뇌사 상태에 빠진 환자에게 돼지 신장을 이식한 결과, 사흘 동안 거부 반응 없이 정상 작동하는 것을 확인했다고 미국 언론들이 보도했다. 연구진은 이식에 앞서 뇌사 환자 가족으로부터 장기 이식 실험 동의를 받았다.

연구진은 돼지 신장을 환자 몸 밖에 둔 채 환자의 혈관을 연결한 뒤 3일간 면역 거부반응과 정상 기능 여부를 관찰했다. 그 결과 이식된 돼지 신장은 즉각적인 면역 거부반응을 일으키지 않았을 뿐 아니라 노폐물을 걸러내고 소변을 만드는 신장 기능도 정상적으로 수행했다. 신부전 증상 지표 중 하나인 크레아티닌도 신장 이식 후 ‘거의 즉시’ 정상 수준을 회복했다고 연구진은 밝혔다.

몽고메리 박사는 장기가 체내에 이식되지는 않았지만 장기가 신체 외부에서 기능한다는 사실은 그것이 체내에서도 작동할 것이라는 강력한 지표라고 ‘뉴욕타임스’에 말했다.

돼지 신장을 사람한테 이식하는 실험은 안전성 문제로 그동안 금지돼 왔다. 픽사베이

_______

유전자 편집으로 돼지의 면역 거부 반응 유발 물질 없애

이번 실험에 사용된 돼지는 면역 거부 반응의 주범인 돼지 세포의 당 분자가 만들어지지 않도록 유전자를 편집한 돼지 ‘갈세이프(GalSafe)다. 갈세이프는 지난해 12월 미 식품의약국(FDA)으로부터 식품 및 의료용으로 써도 좋다는 안전성 승인을 받았다. 이 돼지를 개발한 업체는 리비비코어(Revivicor)로, 1996년 세계 최초의 복제양 돌리를 탄생시킨 피피엘 세라퓨틱스(PPL Therapeutics)에서 분사한 기업이다. 모회사인 생명공학업체 유나이티드 세라퓨틱스(United Therapeutics)는 당시 이 돼지를 이용한 장기이식에 도전할 계획임을 밝힌 바 있다.

이번 실험은 54시간 동안 진행되고 끝나버렸지만, 만성적인 이식 장기 부족을 해소할 수 있는 돌파구에 대한 기대감을 높이고 있다.

‘뉴욕타임스’에 따르면 미국의 경우 신장이 필요한 9만명을 포함해 현재 10만명 이상이 이식 대기자 명단에 올라 있으나, 장기 부족으로 매일 12명이 목숨을 잃고 있다. 또 50만명의 신부전증 환자들은 힘든 투석 치료에 의존해 생존하고 있다.

연구에 참여하지 않은 존스홉킨스의대 도리 세게브 교수는 “이식 장기의 수명에 대해서는 더 많이 알아야 할 필요가 있다”며 “그럼에도 이번 실험은 엄청난 성과”라고 말했다.

그러나 장기 공유 연합 네트워크(United Network for Organ Sharing)의 최고 의료 책임자인 데이비드 클라센 박사는 유전자 조작 돼지의 장기가 살아 있는 인간에게 사용되기까지는 돼지 바이러스 감염 우려 등 많은 장애물이 남아 있다고 말했다.

이종 장기 이식은 오래 전부터 시도돼 왔다. 1960년대엔 몇몇 환자가 침팬지 신장을 이식받아 최대 9개월까지 생존했다. 1983년엔 개코원숭이 심장을 이식받은 소녀가 20일 동안 생존했다.

이후 의과학자들은 키우기가 더 쉽고 6개월만에 성인 몸집 크기까지 자라는 돼지에 주목했다. 그동안 돼지 심장과 신장 이식은 원숭이를 대상으로 해왔으며, 인간을 대상으로 한 이식 실험은 안전상의 문제로 금지돼 왔다.

그러다 식품의약국이 유전자변형 돼지에 대한 의료용 사용 허가를 내줌으로써 이종간 장기 이식 실험의 물꼬를 터줬다.

동물 윤리 문제를 연구하는 헤이스팅스센터의 카렌 마쉬케 박사는 영국 일간 ‘가디언’에 “동물 복지에 관한 우려를 해소할 수 있다면 장기이식용 돼지를 키우는 것이 용인될 수도 있을 것”이라고 말했다.

그는 그렇더라도 다른 이슈가 있다며 이런 질문을 던졌다. “우리가 할 수 있다는 이유만으로 이걸 해야만 할까?”

아래는 2022년 1월 11일 뉴스입니다~

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

유전자 변형 돼지 심장, 사람 이식 첫 성공… “완전히 그의 것이 됐다”

미국 메릴랜드대 의대 연구진이 환자에게 이식할 돼지 심장을 보이고 있다./UMMC

미국 메릴랜드대 의대 연구진은 10일(현지 시각) “말기 심장병 환자인 57세 남성 데이비드 베넷에게 면역거부반응이 없도록 유전자를 변형한 돼지 심장을 이식하는 데 성공했다”고 밝혔다.

이식 수술은 메릴랜드대학병원에서 진행됐다. 8시간의 심장 이식 수술을 집도한 바틀리 그리피스 박사는 “심장 박동도 있고, 혈압도 정상적이며 제대로 작동한다. 완전히 그의 심장이 됐다”며 “매우 흥분된다”고 밝혔다.

연구진은 “베넷은 수술을 받은 지 3일이 지나 건강상태가 양호하다”며 “이번 이식 수술은 유전자를 변형한 동물의 심장이 급성 거부 반응 없이 사람 심장처럼 기능을 할 수 있음을 처음으로 입증했다”고 밝혔다.

베넷은 여전히 심장과 폐를 우회해 산소를 공급하는 체외막산소공급장치(ECMO·에크모)에 연결된 상태이다. 이는 심장 이식 수술에서 일반적인 일이다. 의료진은 새로 이식한 심장이 이미 대부분의 기능을 하고 있으며 화요일 에크모 장치를 끌 수 있을 것이라고 밝혔다.

앞서 베넷은 치명적인 부정맥으로 병원에 입원해 6개월 이상 에크모에 의존했다. 메릴랜드대학병원을 비롯해 여러 이식센터에서 기존 방식의 심장 이식은 불가능한 것으로 판정받았다. 인공 심장 펌프 역시 부정맥 때문에 쓸 수 없었다. 베넷은 수술 전날 “죽거나 돼지 심장을 이식받거나 둘 중 하나였고 나는 살고 싶었다”고 밝혔다.

미 식품의약국(FDA)은 생명을 위협받고 있는 상태에서 다른 방법이 없는 경우에 진행하는 응급 수술로 돼지 심장 이식을 허가했다. 그리피스 박사는 “이식용 장기 부족 문제를 해결하는 데 한 걸음 가까이 간 획기적인 수술”이라며 “세계 최초로 진행된 이번 수술이 앞으로 환자들에게 중요한 새 대안을 제시할 것이라고 믿는다”고 밝혔다.

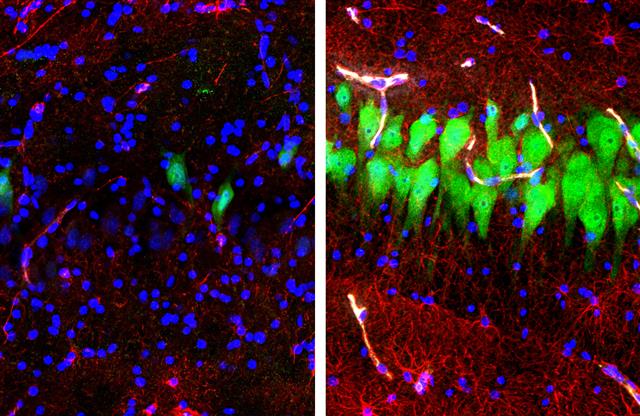

돼지 심장을 이식받은 미국 환자 데이비드 베넷(57)괴 메릴랜드 의대 바틀리 그리피스 박사가 10일 공개한 모습. 베넷은 7일 이식 수술 후 현재 정상적인 심장 박동과 혈압을 보이고 있다고 그리피스 박사는 밝혔다./UMMC

미국 정부에 따르면 현재 약 11만 명이 장기 이식을 기다리고 있으며 매년 6000명 이상이 이식 수술을 받지 못하고 사망한다. 동물의 장기를 사람에 이식하는 이종(異種)장기이식은 수천 명의 생명을 구할 수 있지만 치명적인 급성 면역거부반응을 일으킬 문제가 있었다. 1980년대 캘리포니아대에서 선천성 심장병을 갖고 태어난 아기에게 원숭이 심장을 이식했지만 면역거부반응으로 한 달도 안 돼 사망했다.

과학자들은 일찍부터 미니돼지를 이식용 장기 부족 문제를 해결할 대안으로 주목했다. 장기 이식용 미니돼지는 다 자라도 일반 돼지의 3분의 1 크기다. 하지만 몸무게는 60㎏으로 사람과 비슷하다. 심장 크기도 사람 심장의 94% 정도이고 해부학 구조도 흡사하다. 최근 부분적으로 돼지 장기가 사람에게 이식되고 있다. 돼지 심장 판막은 사람에게 성공적으로 이식되고 있다. 당뇨병 환자는 돼지 췌장세포를 이식받았으며, 돼지 피부도 화상 환자에게 임시로 이식된다.

메릴랜드대 의대의 무하마드 모히후딘 교수는 앞서 돼지 심장을 원숭이에게 이식한 바 있다. 하지만 면역거부반응 때문에 사람에게는 적용하지 못했다. 미국의 재생의료기업인 리비비코어(Revivicor)는 메릴랜드대학병원에 급성 면역거부반응이 없도록 유전자를 변형한 돼지를 제공했다.

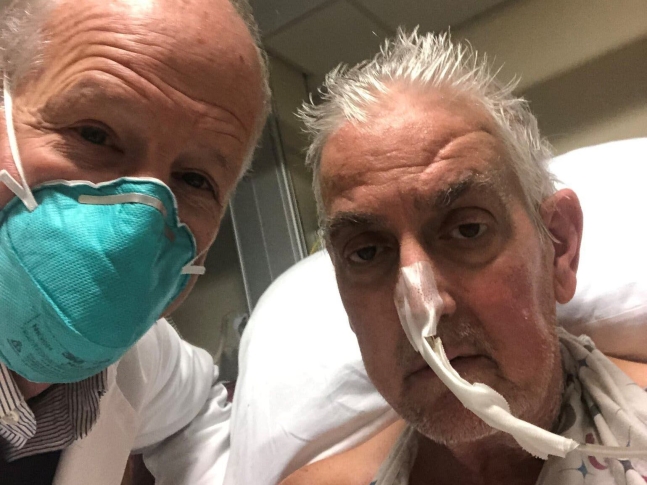

리비비코어는 돼지에 유전자 교정과 복제라는 두 가지 생명공학 기술을 적용했다. 먼저 돼지 유전자 10개를 교정했다. 면역거부반응을 유도하는 유전자 3개는 작동하지 못하게 했으며, 인체의 면역체계를 견딜 수 있도록 유전자 6개를 새로 넣었다. 또 이식한 심장이 더 자라지 못하도록 성장 유전자 1개도 기능을 차단했다. 이렇게 유전자를 교정한 돼지를 복제해 수를 늘렸다. 수술 과정에서 기존 면역억제제와 함께 키니스카 파마슈티컬이 개발한 면역억제 신약도 사용했다.

아래는 2022년 3월 1일 뉴스입니다~

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

돼지 심장 이식 환자, 두달만에 사망… 거부반응 탓인지는 불분명

미국 메릴랜드대학병원에서 지난 1월 57세 남성 심장병 환자인 데이비드 베넷(오른쪽)이 돼지 심장 이식 수술을 받기 전 담당 의사 바틀리 그리피스(왼쪽)와 찍은 사진. /미 메릴랜드대학병원

미국 메릴랜드대학병원은 “데이비드 베넷(57)이 역사적인 돼지 심장 이식 수술을 받은지 두 달 만에 지난 화요일 사망했다”고 9일(현지 시각) 밝혔다.

병원 대변인은 “베넷의 몸이 심장을 거부했는지 불분명하다”며 “사망 당시 명확한 사인은 확인되지 않았다”고 밝혔다. 뉴욕타임스는 “대학병원측이 아직 의사가 정밀 검사를 하지 않았다고 더 이상 언급을 하지 않았다”며 “병원 연구진은 의학 학술지에 검사 결과를 발표할 예정”이라고 전했다.

고인의 아들인 데이비드 베넷 주니어는 “병원 의료진이 아버지를 위해 모든 노력을 다했다”며 “아버지는 실험적인 이식 수술을 받아 의학에 기여했으며 장차 환자들의 생명을 살릴 희망을 줬다”고 밝혔다.

돼지 심장 이식 과정

당시 이식 수술을 집도한 바틀리 그리피스 박사는 이날 “의료진은 베넷씨의 죽음에 망연자실했다”고 밝혔다. 그는 “베넷씨는 죽는 순간까지 병과 싸운 용감하고 훌륭한 환자였다”며 “전 세계 수백만 명에게 살고자 하는 용기와 확고부동한 의지를 보여줬다”고 추모했다.

말기 심장병 환자인 베넷은 지난 1월 7일 미국 바이오 기업 리비비코어가 제공한 돼지 심장을 이식받았다. 당시 베넷은 치명적 부정맥 때문에 입원해 6개월 이상 심장과 폐를 우회해 산소를 공급하는 체외막산소공급장치(ECMO·에크모)로 연명했지만 여러 병원에서 ‘심장 이식 불가’ 판정을 받았다. 미 식품의약국(FDA)은 다른 치료 방법이 없는 경우에 해당한다고 판단해 돼지 심장 이식 수술을 허가했다.

베넷씨가 받았던 이종(異種) 장기 이식 수술은 만성적인 장기 부족 문제를 해결할 대안으로 주목을 받았다. 미국 정부에 따르면 장기 이식 대기자는 현재 약 11만명이며 매년 6000명 이상이 이식 수술을 못 받고 숨진다. 과학자들은 동물 장기 이식, 특히 미니 돼지를 최적의 대안으로 꼽는다. 미니 돼지는 다 자라도 일반 돼지의 3분의 1에 불과하지만 몸무게는 60㎏으로 사람과 비슷하고 심장 크기도 사람 심장의 94% 정도다. 해부학적 구조도 흡사하다. 새끼도 많이 낳아 장기 대량 공급에 유리하다.

베넷에게 이식한 돼지 심장은 미국 바이오 기업 리비비코어가 제공했다. 이 회사는 돼지에게 유전자 교정과 복제라는 두 가지 생명공학 기술을 적용했다. 먼저 유전자 가위(DNA에서 원하는 부위를 잘라내는 효소)로 면역 거부반응을 유도하는 유전자 3개가 작동하지 못하게 했다.

또 인체의 면역 체계에 순응하도록 돕는 인간 유전자 6개는 추가하고 이식한 심장이 더 자라지 못하도록, 성장 유전자 하나는 기능을 차단했다. 이렇게 유전자를 교정한 세포를 복제해 이식용 장기를 공급할 돼지 수를 늘렸다.

미국 앨라배마대 의료진이 지난해 9월 돼지 신장을 오토바이 사고로 뇌사 판정을 받은 남성 짐 파슨스(57)에게 이식하는 모습. 의료진은 1월 20일 미국이식학회저널(AJT)에 수술 결과를 발표했다./미 앨라배마대

돼지 심장 이식 수술은 성공적이라는 평가를 받았다. 수주 동안 아무런 거부 반응도 일어나지 않았다. 베넷씨는 가족과 시간을 보내며 재활치료를 받고 수퍼볼 경기도 시청했다고 병원은 밝혔다. 하지만 사망 며칠 전부터 갑자기 상태가 악화되기 시작했다.

베넷씨가 사망했지만 그럼에도 이식 직후 심장이 초기 급성 면역거부 반응을 보이지 않았고 한 달 이상 정상적으로 기능했다는 점에서 중요한 발전으로 평가되고 있다. 수술 집도의인 그리피스 박사는 “이식용 장기 부족 문제를 해결하는 데 한 걸음 가까이 간 획기적 수술”이라고 밝혔다.

최근 이종 장기 이식에서 잇따라 성과가 나왔다. 지난해 10월 뉴욕대병원 의료진이 뇌사자에게 유전자를 변형한 돼지 신장을 연결해 54시간 정상 기능을 유지하는 데 성공했다. 당시 신장은 몸밖에 연결했다.

지난 1월 20일에는 앨라배마대 의료진이 지난해 9월 뇌사 환자의 몸 안에 유전자를 변형한 돼지 신장을 이식하는 데 성공했다는 연구 결과를 발표했다. 수술 23분 만에 돼지 신장이 소변을 생성하기 시작했으며, 사흘간 정상적인 기능을 보였다. 앨라배마대는 연말까지 실제 환자에게 돼지 신장을 이식하는 임상시험을 시작하겠다고 밝혔다.

한편 베넷씨의 수술 직후 그가 34년 전 한 사람을 칼로 찔러 반신불수로 만든 범죄인이었다는 사실이 밝혀져 논란이 됐다. 희생자는 평생 휠체어에 살다가 2007년 세상을 떠났다. 베넷은 6년을 복역하고 1994년 석방됐지만 희생자가 사망할 때까지 보상금을 다 내지 못한 것으로 알려졌다. 이에 대해 메릴랜드대학병원은 “환자는 절실히 필요한 상황에서 우리에게 왔고, 병원은 의료 기록만을 근거로 이식 자격에 관한 결정을 내렸다”고 밝혔다