(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

‘세기의 특허 전쟁’으로 불리던 미국 브로드연구소와 UC버클리 사이의 유전자가위 ‘크리스퍼’ 특허 분쟁이 결국 브로드연구소의 승리로 끝났다. 이로써 3년 넘게 끌어온 두 연구팀 사이의 특허 소송이 공식 종료됐다.

미국연방항소법원은 10일 “진핵세포(미생물 외에 동식물을 포함하는 보다 복잡한 생물군)를 대상으로 한 브로드연구소의 유전자가위 크리스퍼 관련 발견은 충분한 증거에 의해 뒷받침되고 있다”며 “UC버클리의 주장도 검토했지만 설득력이 없다고 결론 내렸다”고 브로드연구소의 손을 들었다. 미국연방항소법원 또는 미국연방순회항소법정은 우리의 고등법원에 해당하지만, 미국은 연방대법원까지 가는 사건이 거의 없어 이번 판결이 사실상 마지막 판결이 될 것으로 보인다.

두 연구팀은 2014년부터 특허 분쟁을 벌여왔다. 제니퍼 다우드나 미국 UC버클리 화학과 교수와 당시 같은 연구실에 있던 에마뉘엘 샤르팡티에 박사(현 독일 막스플랑크 감염생물학연구소장)팀은 2012년 미생물의 면역 시스템인 크리스퍼와 절단 단백질 캐스나인(cas9)을 활용해 미생물 유전자를 정밀 교정할 수 있는 크리스퍼-Cas9를 처음 고안했다. 다우드나 박사는 크리스퍼 기술의 잠재성을 알아보고 바로 미국에 특허를 출원했다.

UC버클리의 독주 무대였던 상황은 2014년 변했다. 미국 MIT와 하버드대가 공동설립한 브로드연구소의 펑장 교수팀이 진핵생물(미생물이 아닌 동물, 식물 등을 포함하는 생물군)에 적용할 수 있는 본격적인 크리스퍼-캐스9 기술을 개발해 특허를 출원했다. 이 과정에서 펑장 교수팀은 미국의 신속심사제도를 이용해 앞서 특허를 출원한 UC버클리 팀보다 먼저 특허 심사를 받았고, 결국 2017년 먼저 특허를 취득했다(UC버클리 팀은 올해 특허를 취득했다).

2014년 신속심사를 통한 특허 출원 사실이 알려지자 UC 버클리 팀은 곧바로 자신의 특허가 침해 받았다고 이의를 제기했다. 하지만 2017년 4월 미국 특허청은 “브로드연구소의 연구 결과가 독자적으로 특허를 받을 수 있는 충분한 자격을 갖췄다”고 판정했다. UC 버클리팀은 이에 불복해 항소했고, 10일 결국 1심 판결을 유지한다는 결정이 내려졌다. 이번 판결로 UC 버클리팀의 특허와 별개로 브로드연구소의 특허가 독립적으로 유지되게 됐다.

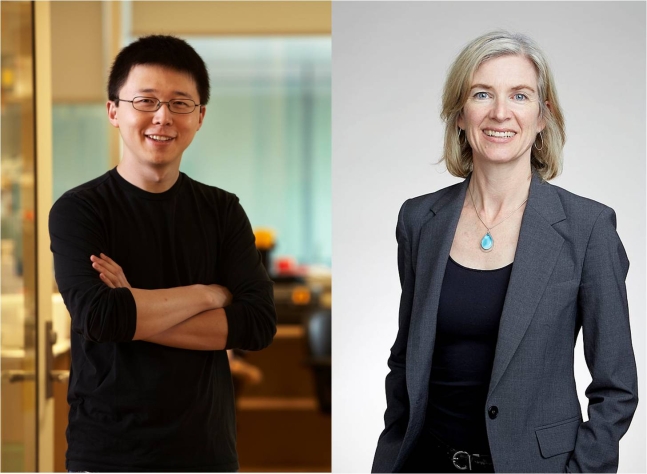

이번 소송에서 승리한 펑 장 MIT 교수(왼쪽)와 상대쪽이었던 제니퍼 다우드나 UC 버클리 교수(오른쪽)

브로드연구소는 곧바로 성명을 발표해 “올바른 결정이 내려졌다. 우리와 UC버클리는 특허와 응용 분야가 다르며 서로 충돌하지 않는다”며 환영의 뜻을 밝혔다. 반면 UC 버클리 팀은 따로 공개적인 입장을 밝히지 않았다.

크리스퍼는 유전체(게놈)의 특정 DNA를 정확히 찾아 잘라낼 수 있는 정밀 유전자 교정 기술이다. 농축산업에서 수확량이 많거나 병충해에 강한 작물 또는 가축을 만들 때, 유전병을 치료할 때 등에 활용 가치가 커 ‘원천기술’을 좌우할 이번 특허에 관심이 많았다.

크리스퍼 기술도 개발 6년이 지나면서 많이 진화하고 있다. 기술도 변화했고 새로운 활용 방법도 발견되고 있다. 제니퍼 다우드나 교수는 지난달 기자와의 e메일 인터뷰에서 “캐스나인 대신 캐스12 a 등 다른 단백질을 이용해 인간유두종바이러스(HPV)를 정확하게 진단하는 기술을 개발했다”며 “감염병 진단에도 크리스퍼가 활약할 것”이라고 밝히기도 했다.

한편 한국에서는 대표적 크리스퍼 전문가 김진수 기초과학연구원(IBS) 단장이 크리스퍼 관련 기술에 대한 특허를 서울대에서 자신이 세운 기업 툴젠으로 이전하는 과정에서 적절한 절차를 밟지 않았다는 주장이 제기돼 서울대가 조사에 들어갔다. 이 같은 주장에 대해 서울대와 툴젠은 “2012~2013년 당시 적법한 절차에 따라 특허권이 이전됐다”는 반박 입장을 밝힌 상태다.

The CRISPR patent decision didn’t get the science right. That doesn’t mean it was wrong

The CRISPR patent decision didn’t get the science right. That doesn’t mean it was wrong

The CRISPR patent dispute between the University of California, Berkeley, and the Broad Institute is finally over. As almost everyone following the case predicted, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit affirmed Monday the U.S. patent office’s decision that there was “no interference-in-fact” between UC Berkeley’s patent application and more than a dozen Broad patents. In plain English: Broad researcher Feng Zhang’s CRISPR patents were sufficiently inventive over the UC Berkeley’s patent applications with Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier.

Many scientists disagree with the decision, believing that it fails to comport with how molecular biology is actually practiced. I agree with them. But that doesn’t make the Federal Circuit’s decision wrong. In fact, I think its decision is absolutely correct.

The reason has to do with standards of review — the standards courts use to weigh evidence, limit their authority, and make decisions. Like criminal law’s “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard, standards of review are incrediblyimportant for many legal cases. They’re how much one side needs to prove something and, failing that, who should win.

The standard of review in the CRISPR patent dispute was the “substantial evidence” standard: whether a reasonable trier of fact (one or more people who determine the facts in a legal proceeding) based its opinion on substantial evidence. To be clear, that doesn’t mean the trier of fact got things correct, or even whether there was more evidence for the other side. Rather, the substantial evidence standard means only that a fact-finder based its decision on substantial enough evidence to be reasonable.

And there was substantial enough evidence for the Patent Office to determine that Zhang’s application of Doudna and Charpentier’s CRISPR-Cas9 system, which they developed in bacteria, to more complex eukaryotic cells (cells like human cells that have nuclei) constituted a significant enough advance to be its own invention. The patent office considered the scientific difficulties in getting other nucleic acid gene-editing systems to work in eukaryotes; statements submitted by experts from both sides, such as UC Berkeley’s own expert saying that there was “no guarantee that Cas9 would work effectively on a chromatin target or that the required DNA-RNA hybrid can be stabilized in that context,” and ultimately statements by Doudna herself that called the gap between bacteria and human cells a “huge bottleneck.”

I, and many scientists as well, think that holding these offhanded statements against Doudna is both unfortunate and bad as a matter of policy. But they were evidence, and the patent office was correct to consider them as such. Considered as a whole, those statements, the testimony of experts, and scientific difficulties in getting previous gene-editing systems to work in eukaryotic cells represent at least substantial evidence.

This doesn’t mean I agree with the patent office’s interpretation of the science. In its original decision, the patent office wrote that moving previous gene-editing systems from bacteria to eukaryotic cells suffered from numerous problems: “differences in gene expression, protein folding, cellular compartmentalization, chromatin structure, cellular nucleases, intracellular temperature, intracellular ion concentrations, intracellular pH, and the types of molecules in prokaryotic versus eukaryotic cells.”

These problems were real and shouldn’t be discounted. But, as I wrote in article for EMBO Reports last year, they were widely known to scientists at the time who could have solved each with a road map of solutions. “[D]ifferential gene expression can be controlled by selecting appropriate promoters; protein folding can, in some instances, be made uniform by certain optimization techniques; chromatin structure can be altered by histone modification; nucleases can be blocked; temperature can be regulated; pH can be buffered; and so on,” I wrote. As a matter of patent law, however, this experimental road map isn’t enough — it does not provide, in patent parlance, a “reasonable expectation of success.”

This illustrates, I think, a classic disconnect between the legal standards of patent law and the realities of scientific research. There are others, which I have also written about at length: on how science and patent law treat reproducibility; how they treat genetic datasets; on what, exactly, is a “law of nature.”

You could say that as a former laboratory scientist turned patent law professor, this is a particular academic interest of mine. But my view of what’s best is not the same as what the law actually is. The CRISPR patent decision may not have gotten the science right. But that doesn’t make it wrong as a legal matter.

If you don’t agree with the Federal Circuit’s decision, you may be in good company. The law can sometimes be wrong as a matter of both policy and practicality. But, at least ideally, the law provides a previously agreed-upon, neutral set of rules to decide disputes. When the law no longer works, it’s ultimately the job of Congress to change the law. And although this ideal is routinely flaunted in practice, it’s still a model to live by.

In fact, it’s something scientists themselves should be familiar with. When the facts stop fitting the model, you change the model, not the facts. You dust yourself off, come up with new hypotheses and new experiments to explain the world, and try again.

Jacob S. Sherkow, J.D., is professor of law at the Innovation Center for Law and Technology at New York Law School.

아래는 2022년 3월 7일 뉴스입니다~

(원문: 여기를 클릭하세요~)

유전자가위 노벨상 수상자, 7년 특허 소송서 패배

미 특허심판원, 경쟁 연구소쪽에 특허권 인정

“진핵세포에서 먼저 기술 성공한 건 펑장 팀”

유전자가위 ‘크리스퍼-카스9’ 기술 특허를 놓고 분쟁 중인 2020년 노벨상 수상자 제니퍼 다우드나(왼쪽)와 펑장. 위키미디어 코먼스

유전자가위 크리스퍼-카스9(CRISPR-Cas9)을 개발한 공로로 2020년 노벨화학상을 받은 제니퍼 다우드나 교수가 정작 그 기술을 둘러싸고 벌어진 특허 소송에서 패하고 말았다.

미국 특허상표국(USPTO) 특허심판원(PTAB)은 7년간 이어진 크리스퍼 특허소송 항소심에서 지난달 28일 최종적으로 다우드나가 속한 버클리캘리포니아대(UC버클리) 연구팀이 아닌 MIT-하버드브로드연구소의 펑장 교수팀 손을 들어줬다. 이 기술의 핵심이라 할 진핵세포 크리스퍼 기술에 대한 다우드나쪽의 지적재산권 주장을 기각했다.

과학저널 ‘사이언스’에 따르면 특허심판원은 판결문에서 인간을 포함한 진핵세포에서의 유전자편집 기술을 실질적으로 향상시킨 쪽은 브로드연구소 팀이라고 판단했다. 이는 크리스퍼에 기반한 의약품을 개발하는 기업들은 앞으로 브로드연구소쪽과 기술사용료를 협상해야 한다는 걸 뜻한다.

이에 따라 펑장 교수팀은 노벨상 수상의 영예를 함께하지 못한 대신 거액의 로열티를 챙길 수 있는 실리를 손에 넣게 됐다. 반면 다우드나 교수가 공동창업자로 참여한 생명공학기업 인텔리아 세라퓨틱스는 큰 손실이 불가피하게 됐다. 특허심판원의 판결이 나오던 날, 크리스퍼 주사를 이용한 치료제로 신경장애 치료에서 큰 성과를 거뒀다고 발표한 인텔리아는 패소 소식이 전해지면서 주가가 급락했다.

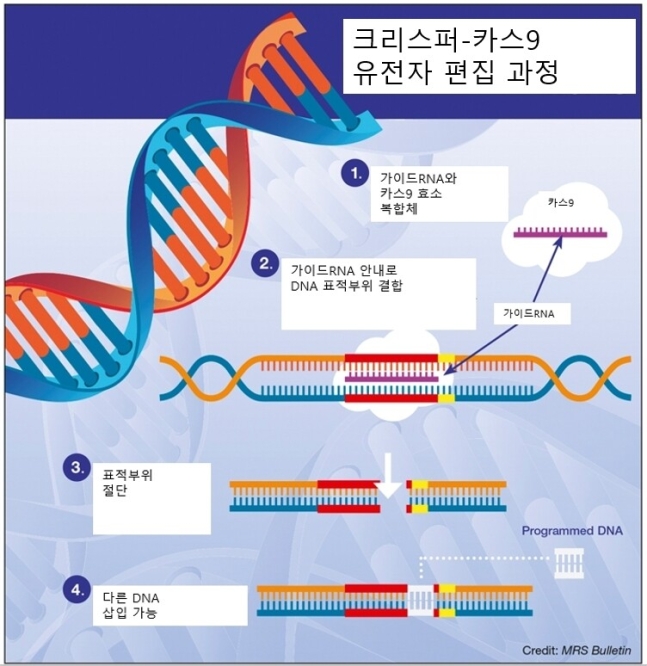

분쟁의 씨앗은 10년 전에 뿌려졌다. 다우드나 교수는 노벨상 공동수상자인 엠마뉘엘 샤르팡티에(독일 막스플랑크연구소)와 함께 2012년 6월28일 ‘사이언스’에 ‘크리스퍼-카스9’이란 이름의 유전자가위 기술을 발표했다. 박테리아의 바이러스 면역 시스템에서 힌트를 얻은 이 기술은 유전자가위를 DNA의 표적 부위로 데려다 주는 가이드RNA(크리스퍼)와 표적을 잘라내는 효소 단백질(카스9)으로 구성돼 있다. 따라서 이 도구를 이용하면 유전체에서 원하는 부위만 골라 절단할 수 있다.

그러나 당시 다우드나팀은 이 기술을 세포 안에서 시연해 보이지는 못했다. 세포 안에서 이 기술을 처음 시연해 보인 것은 브로드연구소의 평장 연구팀이었다. 이들은 2013년 1월3일 ‘사이언스’에 인간과 생쥐 세포를 대상으로 한 연구 결과를 발표했다.

다우드니팀은 2012년 5월, 펑장팀은 2012년 12월에 특허를 출원했다. 각각 자신들의 논문이 발표되기 한 달 전이다. 그런데 특허를 먼저 받은 것은 2014년 4월 브로드연구소팀이었다. 신속심사 제도를 적극 활용한 덕분이었다. 이후 이듬해 다우드나팀이 브로드연구소의 특허에 이의를 제기하면서 기나긴 특허 싸움이 시작됐다.

특허심판원은 7년간의 분쟁을 끝내는 84쪽짜리 판결문에서 어류와 포유류 세포를 대상으로 실시한 두 그룹의 실험을 검토한 끝에, 브로드연구소팀이 2012년 10월5일 이전에 세포를 대상으로 한 유전자가위 실험에서 성공했다고 결론을 내렸다.

다우드나쪽은 브로드연구소가 자신들의 기술에 기반해 성공한 것이라고 주장했으나, 심판원은 받아들이지 않았다.

미국 버지니아주 알렉산드리아에 있는 특허상표국 본부 건물. 위키미디어 코먼스

특허심판원 판단의 핵심은 UC버클리의 기술은 원핵세포, 브로드연구소의 기술은 진핵세포에 적용된다는 것이다. 이것이 중요한 이유는 이 기술을 실제로 사용하는 대상이 대부분 인간을 포함한 진핵세포이기 때문이다.

버클리캘리포니아대는 판결 직후 성명에서 “우리는 특허심판원의 결정에 실망했으며 크게 실수한 것이라고 생각한다”며 이번 판결에 이의를 제기하는 다양한 방안을 검토하고 있다고 밝혔다. 성명은 또 “다우드나팀은 크리스퍼 기술의 다른 부분에 40개 이상의 특허를 보유하고 있으며 30개국에서 원천기술 특허를 확보했다”고 덧붙였다.

브로드연구소는 “특허심판원과 연방법원이 거듭 확인한 것처럼, 브로드의 진핵세포를 대상으로 한 기술은 엄연히 다른 특허이며 시험관 실험 결과로부터는 얻기 어려운 것”이라고 밝혔다. 브로드연구소는 또 비용이 많이 드는 특허분쟁을 끝내기 위해 오랫동안 다우드나쪽과 공동라이선스 계약을 추진해왔다고 덧붙였다.

일리노이대 제이콥 셔코(Jacob Sherkow) 교수(법학)는 ‘사이언스’에 “다우드나팀은 정말 좋은 임상시험 데이터를 갖고 있지만 특허가 없고, 브로드팀은 정말 좋은 특허를 갖고 있지만 임상 데이터가 많지 않다”며 두 당사자가 서로 원하는 것이 있는 만큼 원만하게 합의할 수 있는 지혜를 발휘할 수 있을 것이라고 말했다. 그러나 그도 “상어들이 서로 협력하도록 하는 건 어렵다”고 덧붙였다.